Stability, Sustainability and Success in the Sahel: The Next Steps for the Czech Engagement

paper

As a follow-up up to the military involvement of the Czech Republic in the region since 2013 and the consequent rural development projects there, the whole-of-government strategy towards the Sahel (G5) is an expression of responsibility and responsiveness to the related security challenges for the European Union and its African partners. By subscribing to the securitydevelopment nexus, Czechia recently reinforced its diplomatic presence in the Sahel and spread its activities to the areas of health, migration and civil society. To make its contribution to the Coalition for the Sahel sustainable and complementary to the EU’s efforts, Czechia should update its national strategy to build the Sahel’s forward resilience, expand the governance and development pillars and mainstream human rights and gender. It should also improve the financial planning and mainstream the Sahel in the current budget lines to mobilise domestic expertise, gain public support for the Strategy’s longterm implementation and give credence to the Sahel as a priority during the upcoming Czech presidency of the EU in 2022.

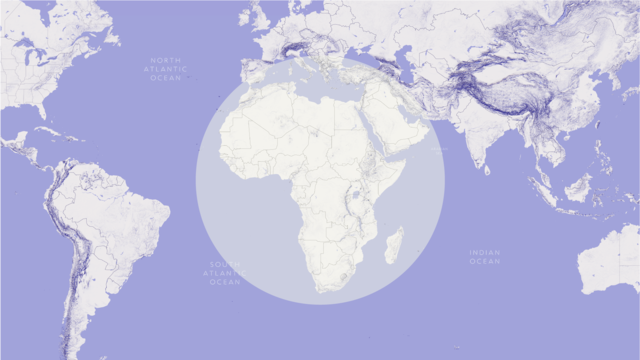

NEIGHBOURS CLOSER THAN EVER

The relations of the Czech Republic with Africa have never been as intense as they are today. In spite of a century of ups and downs since the establishment of the first Czechoslovak diplomatic missions in Alexandria in 1920 and in Cape Town in 1926, Czechia now has 13 Embassies both North and South of the Sahara. It is involved in dozens of development projects and in spite of a 17% decrease due to COVID-19, its trade turnover with the continent still reached almost 3 billion euros in 2020 (see Czech engagement with Africa in figures).

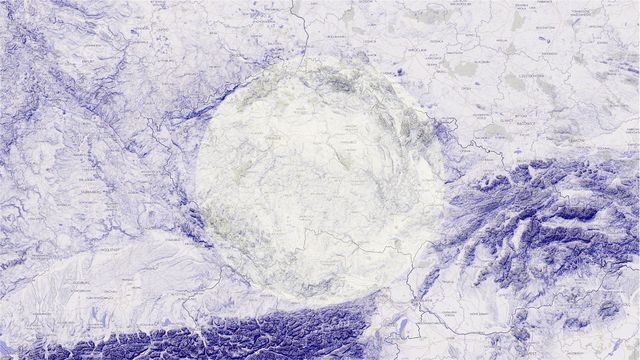

The year 2013, however, marked a substantial shift in the Czech foreign policy towards Africa. As an expression of European and global interests and responsibility, the Czech armed forces joined the EU training mission (EUTM) and then the UN peacekeeping mission (MINUSMA) in Mali. 2018 further saw the adoption of a whole-of-government strategy towards the Sahel (understood here as the G5 Sahel), thus confirming the new geographical priority of the Czech foreign policy beyond the involvement in the security sector.

Globally Czechia ranks among the top eight countries in the SDG Index, but harnessing the expertise and capacities of a small/medium-sized EU member state to establish a partnership with the countries of the Sahel to the benefit of their inhabitants is a challenge. Despite a legacy of the Czechoslovak involvement in the anti-colonial struggle, the Czech relations with Francophone sub-Saharan Africa had not been particularly strong and Czechia has to find its right spot along with other European and global actors beyond the self-proclaimed transition experience.

Accordingly, this policy paper proceeds in three steps. First, it gives an overview of the intertwined security, development and political challenges and opportunities in the five countries of the Sahel. Second, it reviews the Czech security sector involvement in the region and the follow-up moves to implement a broader and more comprehensive government strategy. Finally, with the upcoming rotating EU Presidency, which Czechia will hold alongside France and Sweden, in mind, it offers recommendations to the Czech government to enhance its contribution to assisting the Sahel on its path towards a stable, sustainable and successful future.

STABILITY AND SECURITY

The Sahel has been commonly described as one of the most fragile regions of the world, as it has been suffering from a series of crises that over the past decade resulted from the complex conjunction of both global and local trends. The fragility of governments in the region has longer and deeper roots in the history of colonial and post-colonial state-formation, widespread poverty, tensions between different ethnic groups and clans and climate-related issues. However, the increased international concern with the security and stability of the Sahelian region and arguably also a faster unravelling of the regional order came with the Tuareg uprising in northern Mali in 2012, followed by the collapse of the Malian state and the regional ascent of jihadists and other violent non-state actors accompanied by an intensification of migration flows to Europe.

The security situation remains precarious and has been even worsening in some parts of the region. Significant parts of the Sahelian countries are still outside of the control of the respective state as the conflicts shifted to previously stable areas. The initial successes represented by the French campaign against jihadist forces in northern Mali and the following political reconciliation between the Malian government and the northern separatists, have transformed into a painstakingly slow implementation process. Meanwhile, the general state weakness and the endurance of the Islamist networks instead paved the way to a new wave of insurgencies, terrorist incidents and attacks on civilians in central and recently also in southern Mali, northern Burkina Faso, western Niger and beyond. Further compounding the security crisis in many parts of the region, deep-rooted smuggling and crime networks have intermingled with insurgents and other militants to create alternative political authorities challenging the state authority and each other. Al-Qaeda and recently also Islamic State-linked Jihadist fighters have then often fuelled and fed off these primarily local conflicts and tensions between different identity groups.

However, popular dissatisfaction with the lack of provision of public services, the continuing insecurity, and the heavy-handed operations carried out by national armed forces has contributed to the appeal of diverse violent non-state armed actors and made the re-establishment of the legitimate state authority an increasingly difficult task. In many cases, various rumours and types of disinformation further helped to erode the trust in the national authorities and their international backers. The discontent with the national leaderships in various Sahelian countries reaches beyond open conflicts, and any serious attempts at stabilization need to take these fragile underpinnings of the state-society contract into account. The public response to the August 2020 military coup in Mali and the weeks of popular protests that preceded it have exposed the extent of popular anger with the state’s governance failures, ranging from the lack of public services to the abuse of political power, especially in terms of corruption and impunity.

Mali has been thrown into political turmoil by another coup in May 2021, but criticism of local political elites, which has occasionally spilled over into popular demonstrations, has been mounting also in other countries of the region, namely in Niger and Chad. The aftermath of the death of long-time Chadian president Idriss Déby shows that the relations between authoritarian rule and stability are not straightforward. However, the challenges to stability that the regional authorities were forced to deal with in the past years have been enormous. They range from the needs of almost three million internally displaced persons (IDPs) and refugees in Mali, Niger and Burkina Faso alone to the impact of conflict and the recent coronavirus crisis on food security and local economies more broadly.

Multiple forms of external intervention and assistance have been launched to tackle these multifaceted security crises, which led some analysts to even speak of a ‘traffic jam’ of external involvement. Since 2014 France has borne the brunt of most of the counterterrorism operations in the region. Several European states committed their special forces also to an emerging complementary mission with a combat mandate – the Takuba Task Force – that is supposed to internationalise the counterterrorism efforts and demonstrate the shared European responsibility for the security and stability of the Sahel region. Furthermore, France (and to a lesser degree also other EU countries) has (have) been instrumental also in supporting the formation of a regional counter-terrorism force, the G5 Sahel Joint Force (Force conjointe, FCG5S), that has recently become operational despite numerous logistical and operational hurdles.

The UN peacekeeping mission MINUSMA has been engaged in a wide range of tasks since 2013, from supporting the peacebuilding processes and protecting Malian civilians in the areas with an active presence of insurgents to strengthening the authority of the government over the contested parts of the country, in recent years specifically those in the central regions. Finally, the EU has been involved in the region through its assistance missions that seek to train Malian armed forces (EUTM), or to build the capabilities of the police and other internal security forces in Mali and Niger (EUCAP Sahel Mali, EUCAP Sahel Niger). The support and training of the local armed forces has then been declared as one of the pillars by the Coalition for the Sahel, which has sought to merge security and development initiatives.

The international interest in the Sahel also reflects the emerging geopolitical importance of the region. Although it is traditionally perceived as a predominantly French domain of control and influence, recently there has been a wider range of European states involved in it, including Central and Eastern European countries, such as Czechia or Estonia, showing that the stabilisation of the Sahelian countries has become an all-European issue and a matter of priority. Counter-terrorism efforts have been pursued also by the

US, which under the Biden administration promised to step up support for the French forces and its general involvement in the region. There are also growing concerns of a direct geopolitical competition between the EU and its competitors. Russia has made limited steps in Mali and retains an influence in the information sphere as well as on the fringes of the region in Algeria and the Central African Republic. On the other hand, China has established itself in the Sahel much more strongly with its contributions to MINUSMA, financial support for the G5 Sahel Joint Force, and infrastructural, humanitarian and development projects and its economic role is forecast to be accelerated by the pandemic.

SUSTAINABILITY AND ECONOMY

As they suffer not only from security crises, Niger, Chad, Mali and Burkina Faso also rank among the bottom seven countries of the Human Development Index. The Sahel is therefore given as a foremost example of the nexus between insecurity, poverty and the climate crisis. Many of the local conflicts are often portrayed from a Malthusian perspective as an inevitable result of a fight for scarcer resources of a growing population. In Mali alone, 80% of livelihoods depend on agriculture. With the changing climate, the Sahel’s food production is particularly affected by increasing warming and extreme weather, especially droughts. These translated into generally lower yields for settled farmers and a limited availability of grazelands and water for the larger herds of Sahelian pastoralists (60% of the population keeps livestock).

However, the sharp portrayal of a climate-induced farmer-herder clash in the Sahel, often drawn along ethnic (Fulani vs. others) and religious (Muslim vs. Christian) lines, is too simplistic and reductionist. Indeed, there is a large variability and complexity of agricultural livelihoods there – from sedentary farmers through transhumant semi-pastoralists to nomadic herders and even hunters – that may transcend other social differences. Most families also get engaged in economic activities outside agriculture. Moreover, the effects of climate change are not uniform: food productivity has generally kept up with the population growth not only thanks to the expansion of cropped areas, but also due to the increased rainfall in some Southern regions, and thus pastoralists were harmed more than farmers. Especially Mali has doubled its crop production over the last decade thanks to the state intervention.

However, economy and environment cannot be separated from politics. Pastoralism and livestock production, which are unevenly located closer to the Sahara throughout the region, have been a victim of a strong development bias towards crop production, and especially towards cotton for export, on the part of both national governments and international aid donors for long decades. All these external interventions have put stress on the resilience of informal and multi-layered institutions in the complex, transnational political ecology of the management of natural resources in the Sahel. Moreover, current anti-terrorist and anti-pandemic measures further limit transborder mobility and hence they put further limits on nomadic pastoralism as one of the most sustainable lifestyles on the planet.

As already emphasised from the security point of view, the large number of IDPs and refugees have put further stress on public and environmental services and resources: more than five million people are expected to fall into a severe food insecurity during the summer of 2021 lean season in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger alone, and the corresponding number could possibly reach up to 24 million in Western Africa as a whole. While food production and distribution are immediate priorities, the region will not make it without humanitarian aid for many years to come. The geographical dispersion of the Sahel does not make it easier to provide the population with the necessary infrastructure. Access to electricity is still problematic, though especially Mali did a good job at providing it to 85% of the urban population. However, the urban/rural divide is deep everywhere and with missing off-grid solutions, access to electricity is almost inexistent in rural Mauritania and Chad.

Consequently, rural poverty combined with forced migration may further accelerate the Sahel’s relatively low urbanisation, especially since economic growth shifted to towns and cities from rural areas since the early 2000s . Yet without the provision of education, health services, water and energy in towns and relieving the stress on their environment, urban poverty and inequality may be on the rise soon. While agriculture is essential for sustainable stability and growth, it can hardly make the Sahel profit from its population dividend. While in Mali 300,000 young people enter the labour market each year, only one in six find their job in the formal economy. The current G5’s population of 85 million is expected to increase by 60% within 25 years. Meanwhile, the value added of manufacturing is decreasing throughout the region and nowhere does it exceed Burkina Faso’s figure of 20% of the national product.

Industrialisation in a post-colonial setting is a just but difficult long-term goal: all countries of the geographical Sahel except Senegal are Least Developed Countries (LDCs) and, in addition to that, all the G5 countries except Mauritania are landlocked, which further complicates their fair integration into the African and global economy in spite of their relatively low public debt. The advantages from their geographical location are double-edged. Illicit income from the trafficking economy undermines the state, and the benefits of participating in international migration are limited since the development contribution of remittances is minor in the region, except for Mali. Similarly, the income from exporting natural resources, notably oil and gold, has been volatile and variable, which makes it a difficult base for sustainable growth. Yet, Chad’s rent from natural resources, for example, represents a quarter of its national product, which requires the government to make sure the income is fairly distributed.

SUCCESS AND ACCOUNTABILITY

The Sahel requires a concerted action by local, national and international actors for its growth to be more diversified and inclusive, to become a stabilising factor and to keep up with the high annual population growth in the region, which reaches up to 3.8 % in Niger. However, good governance as the third pillar of the Coalition for the Sahel has shown the slowest progress for several reasons. At the beginning, the European Union’s securitised approach did not make the political dialogue easier because it gave migration a priority status that did not match with the Sahel’s own needs. Moreover, the lack of progress led European actors to a multiplication of initiatives, thus creating an “intervention traffic jam” similar to the one already mentioned in the security field. Finally, the depoliticised approach of the EU to development, its historical patronal relations with Africa and its reluctance to apply any forms of aid conditionality have not offered enough incentives for the Sahelian governments to pursue domestic reforms The positive shift towards more mutual accountability outlined in the new EU’s “Integrated Strategy” for the

Sahel needs yet to be put in practice.

The acclaimed model of the Pôles sécurisés de développement et de governance (PSDGs) in Mali as an expression of the return of the state, also attests a rather reduced understanding of governance as the provision of basic services and mere communication rather than participation. Indeed, successfully resolving farmer-herder conflicts, for example, through enforcement of the existing laws on pastoralism, mediation and involving informal institutions, will be much more difficult since good governance must apply to the state actors themselves to gain the trust of the citizens. Due to weak ownership, the state reinforcement from the EU’s side through EUCAP in Mali and Niger has so far been lagging behind the set objectives. General experience shows that with the rising number of development interventions, badly designed projects, including climate projects, may further exacerbate problems, notably for pastoralists. In the name of security for the local population, do not harm should be the primary development effectiveness principle.

The necessary support for the top-down authority of the state, which is associated with inherent problems such as low capacity and corruption, is not enough, however. It should be coupled with a bottom-up support of the civil society and independent media, which are here understood very largely and as including disadvantaged parts of the population. This can be a delicate task in conflictual societal contexts since the contestation of local authorities in many rural communities is due to stratified caste roles and inequalities. However, especially for European donors, fundamental human rights should be a bottom line and they should strongly support governments in fighting servitude: it is estimated that 500,000 people, including children, still live in conditions described as modern slavery in the G5 countries alone.

Another bottom line for the European actors should be supporting women and girls, whose empowerment is extremely important for achieving any of the economic goals mentioned previously. While the prevalence of female genital mutilation is culturally highly variable, sexual and reproductive health and rights are yet to be met throughout the whole region, and meeting them would allow women and girls to have a better control over their bodies, lives, children, families and work. Child marriage is still frequent in the region, and the figures vary between three in four underage girls getting married in Niger and one in two in Chad. Child marriage is problematic not merely as a breach of a girl’s autonomy, as early marriage is also strongly related to narrow childspacing, maternal and child mortality and high fertility rates (e.g. the fertility rate of almost 7 children in Niger). High natality is not only linked with low education by opportunities, but also with exposure to other forms of genderbased violence. Of course, there is no silver bullet for the violence-healthfertility-education-productivity nexus, but the multiplication effects of women’s empowerment and education of men cannot be underestimated, including the effects on the national wealth. In Mali, for example, female-headed households are already less-likely to be poor than man-headed ones. Real priorities of national and international actors may diverge less in traditional development areas such as water, health and education.

THE CZECH CONTRIBUTION TO STABILITY

The selection of the Sahel as Czechia’s foreign policy priority was initially led more by security than development concerns (see Milestones of the Czech and EU engagement with the Sahel). Indeed, the engagement of the Czech Armed Forces in the Sahel constitutes a significant shift in strategic focus. Historically, Czechia contributed substantially more to only one CSDP mission, EUFOR ALTHEA in Bosnia and Herzegovina (2004-2008), after which it all but pulled out of CSDP military operations, and its participation in expeditionary missions was narrowed down almost entirely to NATO ISAF. When Prague chose to re-engage in these operations, the Sahel became the area of choice. The turning point came in 2013 with the decision to participate in EUTM Mali. The Czech contingents have been tasked with the protection of the mission headquarters in Bamako and the training activities in Koulikoro, but also got involved in combat operations in 2017 when responding to an attack by militants on a hotel resort in Kagaba. The real size of the Czech deployment in EUTM Mali was steadily increased over time from the initial ca. 30 individuals to the current ca. 85.

In 2020, Czechia was tasked with the command of the mission – at this time, the Czech contingent amounted to ca. 115 persons, which was close to the national expeditionary mandate limit of 120 – a duty it performed against the backdrop of two COVID-19 waves impairing the mission’s readiness status that were separated by a coup d’état in August 2020, after which relations with the government, whose legitimacy needed to be determined, had to be re-established; meanwhile a decentralisation of training activities by moving them to Central Mali with the use of other operations’ facilities, took place. The Czech government has expressed its readiness to support the moving of the EUTM’s training centre from Koulikoro to Central Mali (Sévaré), and further regionalisation of the mission in support of the G5 Sahel by expanding its reach to Burkina Faso and Niger. It also outlined an ambition to resume its command of the mission again in the second half of 2022. It has enshrined the support of the regionalisation of CSDP activities in the Sahel among the geographical priorities of the forthcoming rotating presidency of the Council

of the EU.

Furthermore, in the last decade, the Czech Special Forces deployed a contingent in the MINUSMA operation (2015-2016) under Dutch command; the low-key Czech presence in MINUSMA’s command structure has since been continued in view of the prospects of a more substantial future engagement if the available capacities meet with the mission’s force requirements. Moreover, signifying a strategic shift in the Czech engagement in the region, since March 2021, several dozen members of the Czech Special Forces are deployed in Task Force Takuba in Northern Mali alongside French forces engaged in counterterrorist operations, and in support of the G5 Sahel Joint Force combating violent extremist groups as well as at the Takuba mission headquarters (the expeditionary force mandate currently allows for a deployment of 60 troops until the end of 2022). Czechia has also engaged in a bilateral security cooperation with the G5 Sahel countries – with a particular focus on Mali and Burkina Faso. It also contributed to the G5 Joint Force financially during its beginnings.

The Sahel now appears as a prospective destination for potential future deployments, particularly as the expeditionary presence in Afghanistan may terminate in the foreseeable future. The Czech Republic is also supportive of NATO’s increased engagement in the Sahel – which has hitherto been much more limited compared to the EU’s comprehensive toolkit, but outlined in NATO’s Roadmap for the Sahel (2020) – in view of, among other things, the convergence of the U.S. and France on NATO’s role in upgrading the ongoing

activities of member states and bolstering local governments. Fielding civilian experts, e.g. in EUCAP missions, remains impeded (though not prohibitively, as their limited presence in the past shows) due to the scarce local expertise. However, in line with the externalised border paradigm Czechia harbours an ambition in the short term to become involved in the border control and management programmes as much as in civilian CSDP missions.

How can Czechia’s engagement in a territory where it had no previous clearly defined security interests or stable military presence be explained? The assessment of the worsening security situation evidently played a part – as did the framing of the deployments as forward counterterrorism activities and a management of risks posed by the prospective state failure and emergence of a safe haven for Al-Qaeda (AQIM) and its affiliates in the region; and later also the idea of the engagement as a forward strategy to counter irregular migration resonated strongly. However, the progressive winding down of the presence in Afghanistan was a contributing factor too as it enabled resources to be allocated elsewhere and East neighbourhood, the traditional focus area for Czech transition policies, did not provide suitable opportunities for the types of operations the Czech military performed in Afghanistan. Moreover, it was part of a broader engagement in the CSDP – it was later combined with the support for deeper European integration in security and defence, and the EU’s strategic upgrade in general.

Responsivity to French security interests in the Sahel may be also conceived as a hedging of Transatlantic insecurity. This policy was produced first by Obama’s pivoting away from Europe and then by Trump’s disruptive and occasionally erratic presidency against the backdrop of the structural dynamics of the new geopolitical confrontation between the U.S. and China. The move has already resulted in the opening of the strategic dialogue with France as a forum where positions on issues dear to Czech interests elsewhere can be communicated, while in broader terms, the Czech engagement in the Sahel is seen in the national foreign security policy community as projecting an image of a relevant and responsive contributor to the EU’s security even outside the neighbourhood areas of Czechia’s traditional interest (e.g. the Western Balkans) and also vis-à-vis Germany and the Southern member states, as well as a means of its positive differentiation from other Central European countries.

THE CZECH CONTRIBUTION TO

SUSTAINABILITY AND SUCCESS

The Sahel was described as a laboratory of the EU’s integrative approach to security, migration and development assistance. The original focus of the Czech involvement in the Sahel was security but the government has soon subscribed to the nexus thinking and gradually mobilised other foreign, development and migration policy tools. These were consolidated by the Strategy of the Czech Republic to support the stabilisation and development of the Sahel countries for the period 2018–2021, adopted by the government in April 2018. The current comprehensive mid-term report takes stock of the past activities and anticipates their further extension. The whole-of-government strategy, a novel format in relation to a particular region of the world, has no separate budget, but it is closely related to the follow-up adoption of a new inter-ministerial 11 M€ budget line through the Programme of activities to support source and transit countries of migration in Africa 2020–2022 (or the Africa Programme) under the management of the MFA, which mentions the G5 as its main priority.

It is no surprise that the emphasis on migration helped to provide political support for both the Sahel Strategy and the Africa Programme. However, this incremental approach was facilitated by Czechia having the closest ties to Africa out of all the Central and Eastern European countries and its previous experience of coordinating humanitarian aid with the Ministry of Interior’s migration mitigation and prevention programme Aid in Place. This tool started in 2015 with an annual budget of 6 M€ to support, inter alia, border management in the Balkans and refugee camps in the Middle East. While the MFA has a long record of providing aid for the complex humanitarian crisis of the larger Sahel multilaterally, Aid in Place started projects centred on livelihoods of refugees in Chad, Niger and Mali in 2018 and funded an international NGO based in Czechia and several UN agencies to implement them. Czechia has also been active in the G5’s health sector through MEDEVAC by providing local health facilities with equipment and expertise, mostly provided by NGOs with some Czech presence. Altogether the Ministry of Interior spent around 6 M€ in the larger Sahel since 2016.

As the new Africa Programme takes off, the Ministry of Interior’s programme plans to shift towards border management in 2021 with Niger; this shift is premised on the notion of ‘externalised’, forward borders of the EU in the Sahel region. In 2020, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs has dedicated 2.5 M€ to two NGO-implemented projects on food security and basic services for refugees and the rural populations in Mali and Niger; it also financially contributed to other UN agencies. Finally, a new sector where the Czech Republic has a strong record from other world regions is the emerging support of civil society. From 2020, the MFA supports community radio stations in Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger and now in 2021 it also started supporting civil society projects in the region. Finally, the new territorial priority also reflects a new intensity of business relations with the region, ranging from hospital equipment through agriculture to the defence industry. In 2019 Czechia exported goods worth 20 M€ to the G5 countries, it created a new flexible instrument of tied aid to involve Czech companies and it considers adjusting its export credit insurance rules to facilitate trade with the Sahel and setting up its own development bank as a part of the EU’s reform of financial development institutions.

Unlike in Eastern Europe and the Balkans, in the G5, Czechia did not contribute yet with its valued public expertise to improve good governance, its bilateral priority among the Sustainable Development Goals (SDG 16). This is due to the recent re-opening of the Czech Embassy in Bamako in September 2019 – a half-century after Czechoslovakia closed it in 1969 – as only the ninth Embassy of an EU member state in Mali. The full logistical operationality of the Czech Embassy only one year later, the planned increase in personnel and the pending reaccreditation of the other G5 countries attest an institutional delay, but at the same time, it will allow for a deepening of the political dialogue and channel the development projects more directly in the coming years. Czechia also strengthened its diplomatic presence by creating the position of the Special Envoy for the Sahel at the MFA, and as the very first country to do so, it contributed financially to the secretariat of the Coalition for the Sahel.

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Within a span of eight years, the Czech Republic has gradually complemented its support for security and stability with the other pillars of the new-born Coalition for the Sahel and it now makes up a part of the core of countries committed to their partners in the Sahel. The scale of this multifaceted engagement makes Czechia a recognised stakeholder in joint mini- and multilateral activities, where it now aims at responding to the continuing fragility beyond immediate assistance by supporting local civil society, businesses and public institutions in the Sahel. This vision for the near future faces two risks, though.

First, the domestic support for the Czech Army is high and thanks to the underlying migration rationale its mission in the Sahel is so far contested only slightly at the fringe of the political scene. In case of future fatalities in combat missions that Czech soldiers are potentially about to undertake within the framework of Task Force Takuba, however, a possible political backlash can arise. As opposed to the deployments in Afghanistan and Kosovo, for example, there has only been a low-key, mostly expert debate on the Czech involvement in the region so far. Its scope as well as costs might come as a surprise to parts of the public. Furthermore, the potential rapid politicization does not threaten only the military engagement, but also other forms of assistance as the economic shock of the COVID-19 pandemic already brought cuts to the humanitarian and development budget for 2021 in the Parliament.

Second, similarly to the engagement in Afghanistan, the stabilisation of the Sahel will require significant resources over a long period of time.The difficulties that the Czech diplomacy faces in substantially reallocating internal and mobilising external human resources to its political priorities, combined with the limited expertise on Francophone Africa, may lead to “aid fatigue” on the side of the government as well as the public. While involving other organisations and partners is necessary in terms of pooling resources as

well as valuable instrument of building partnerships, if the Czech Republic will continue implementing projects through international and local NGOs while contributing to projects of international organisations, without involving Czech experts, the aid fatigue is expected to grow.

The Czech government should not underestimate these two risks. To mitigate them and make the Czech Sahel Strategy sustainable, public diplomacy and capacity building are not only necessary in regard to decision makers and citizens of the countries of the Sahel in terms of presenting the Czech contribution, but equally so in regard to those living in Czechia as a wide popular legitimacy is a precondition for a durable partnership beyond the double highlight of the Sahel as a priority of the Czech rotating presidency of

the Council of the European Union in the second half of 2022 just after that of France.

Czech decision makers and citizens should be aware that the challenges in the region are highly complex and multidimensional: it is highly likely that there are no quick fixes for them. Any form of serious stabilization and development efforts will most likely take an extended amount of time, and therefore Czechia should start to undertake long-term investments in support of the areas where political, social and economic changes tend to be slow and meet an initial resistance.

- In terms of strategy, the Czech Republic should continue its support for the comprehensive approach in addressing the regional challenges at the national, European and multilateral levels. Czechia should also promote the EU-wide application of the more-for-more principle to incentivise its partners to undertake reforms and take ownership of the European assistance. The updated national Sahel Strategy planned for this year should therefore be aligned to all four pillars of the Coalition for the Sahel and put a stronger emphasis on the restoration of state administrations and development cooperation.

- In the area of stability (Pillars 1 and 2), the strategic engagement should be consolidated and expanded even in the conditions of foreseeable post-COVID strains on public resources. It should include NATO’s supportive activities in addition to enablers and provision of assets such as capacity building, as well as streamlining this approach in Czechia’s bilateral activities. Forward counterterrorism and irregular migration efforts should be complemented by forward resilience to mitigate structural causes of conflict and instability, including inequalities.

- In the area of governance (Pillar 3) and in line with its foreign policy priorities of human rights promotion and SDG 16 (Peace, justice and strong institutions), Czechia should mainstream good governance, participation and rights in all its activities, including capacity building for preventing international humanitarian law breaches and human rights abuses. It should also insist on a consistent application of effective safeguards on the providing of lethal equipment both by the European Peace Facility and bilaterally and ensure that its involvement in border management does not hurt local economies.

- In the area of development (Pillar 4) Czechia also still has to find a niche for its bilateral development cooperation with the Sahel where it could bring extra added value and use its specific expertise from other countries, while balancing its bilateral, European and multilateral contributions. A strong focus on women and girls is a precondition for multiplication effects. The support for capacity building of local civil society organisations is a suitable form of intervention where Czechia has longstanding worldwide experience. At the same time, Czech public institutions should be mobilised to provide their peer expertise and support to their equivalents in the Sahel without intermediaries.

- In terms of financing the Strategy, the Czech government should preserve the flexibility of various financial tools mobilised to implement it, yet at the same time in the 2021 update, it should allocate mid-term budgets estimates that are necessary to reach its goals and allow better planning and budgeting by the involved line ministries. It should also make the Sahel eligible, prioritised and mainstreamed in the existing capacity building, technical assistance, civil society support, public awareness, public diplomacy and training budget lines of CzechAid, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and other ministries – including the emphasis on French as the lingua franca of the region. The updated Strategy should also require more precise reporting of the real expenses in the region.