Triumphalism eroded: Central Europe after the Poland and Slovakia elections

paper

Although the states of Central and Eastern Europe were closely tied in support of Ukraine immediately after the Russian aggression, the results of last year's elections in Poland and Slovakia, together with the rhetoric of their leaders, point to a much more complex position of CEE.

The debate about the center of gravity moving from the continent's west to its east was spurred by the unprecedented support of the selected Central European and Baltic governments for Ukraine. Thanks to its united anti-Russian and pro-Western stance, the hitherto overlooked eastern flank of the EU/NATO was expected to gain a stronger voice in Europe’s geopolitical and geoeconomic turn. However, the political developments in 2023, namely the rhetoric and results of the Slovak and Polish parliamentary elections, held in September and October, respectively, draw a more complex picture.

Such real developments have eroded the moralizing rhetoric of Central European and Baltic “triumphalism”: This triumphalism was articulated by the policymakers and opinion makers inside the region but also by the transatlantic commentariat. It communicates a contradictory but clear message. West European allies were subjected to an often legitimate but also unhelpfully harsh critique for their allegedly immoral and naïve appeasement of Russia. The eastern flank, meanwhile, was (self-)praised as the West’s only willing vanguard in supporting Ukraine and European values against Russian imperialism. Finally, despite the Hungarian reminder, the ritual emphasis on being “united” has neglected the existing internal diversity of political and public views across the region and in individual states.

This chapter uses the elections and the early signals of the new governments in Poland and Slovakia to recognize the reality of Central Europe’s complexity as a foreign policy dilemma that can no longer be fixed by a triumphalist rhetoric. We recommend pragmatically embracing the region’s heterogeneity as an opportunity to form a more pluralist but also sustainable approach to Ukraine, and the EU enlargement and reform.

Central Europe’s triumphalism eroded

The elections and the new governments in Poland and Slovakia provide two sides of the same triumphalist problem. Not only have they exposed the real ruptures in the rhetorical unity of Central and/or Eastern Europe, articulated as an Eastern moral primacy and a decision-making leadership of the East that replaces the reluctant Western Europe, but they show that domestic politics should be taken more seriously as it makes the region multi-faceted rather than united in foreign policy approaches.

Poland’s elections show the two moralist risks of triumphalism, often articulated against other states and/or domestic opponents. First, illiberal triumphalism characterized the governments of Prime Minister Mateusz Morawiecki and Jaroslaw Kaczyński’s Law and Justice (PiS). Second, there is also a risk of liberal triumphalism surrounding the victorious coalition of three election groupings, namely Donald Tusk’s Civic Coalition, the Third Way, and the Left. In reverse, announcing that “Poland is back” in Europe and its mainstream, it simultaneously risks marginalizing the past successes and voices of the new illiberal opposition in rhetoric, and disappointing the unrealistic liberal expectations in practice.

As it has been isolated in the EU decision-making since long ago, PiS’s election campaign made Poland’s illiberal triumphalism implode, including in regard to the Ukraine question. Especially the so-called grain crisis, which grew from the understandable response to domestic fears of Ukraine’s cheap agricultural imports, was escalated into a petty trade conflict. Although escalated by both sides, Morawiecki’s claims that Poland “no longer transfers weapons to [Ukraine]” trashed Poland’s credentials as a leading voice in support for Ukraine.

At the same time, Tusk’s new government brings exaggerated expectations of the country’s return to the European mainstream. Although Tusk is ready to confront politicians “from other Western countries,” the new government will engage with the EU decision-making without searching for friend-enemy conflicts with other allies. However, the domestic context will still matter. The new four-party coalition government is multi-voiced, forced into cohabitation with the PiS-affiliated President Andrzej Duda, and confronted by a fragmented, yet illiberal parliamentary opposition accounting for 42.5% of the votes.

In Slovakia, a reverse shift could be observed – from an alleged liberal turn to an illiberal self-marginalization. Slovakia experienced its own return-to-Europe moment during the 2019 presidential and the 2020 parliamentary elections. The newly formed coalition government, which includes the radicalized Robert Fico’s SMER and the far-right Slovak National Party, are thus a blast to the moralist rhetoric about Slovakia becoming a “decent” European country again.

Fico’s government heralds an anti-Ukrainian turn in the Slovak foreign policy approach. What is more, the potential run against the judiciary system might risk repeating the agony of Hungary and Poland’s past conflicts over the rule of law with Brussels. One might witness an illiberally-oriented self-marginalization under this government. Gaining 18% of the votes, the new liberal opposition party Progressive Slovakia might play the role of a countervailing force, although its capacity to do so has proved rather limited so far.

The centre of gravity no more

Put simply, the notions of Central Europe and the Eastern flank cannot be rhetorically forced into a unified front against a common opponent, be it Brussels or Moscow, or for a common cause, e.g., the Ukrainian one. Once the echo chambers of Central European triumphalism and the centre-of-gravity debate leave, one can find opportunities for a more pluralist and balanced cooperation within the region and vis-à-vis the rest of Europe.

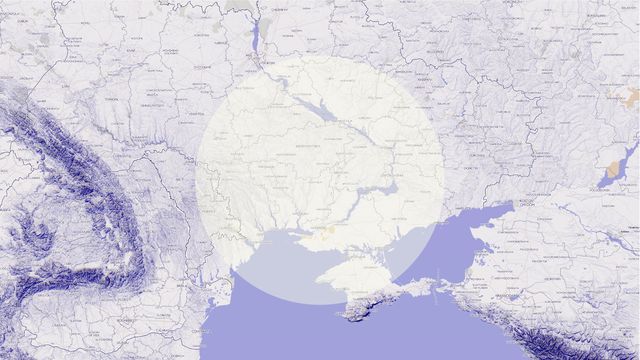

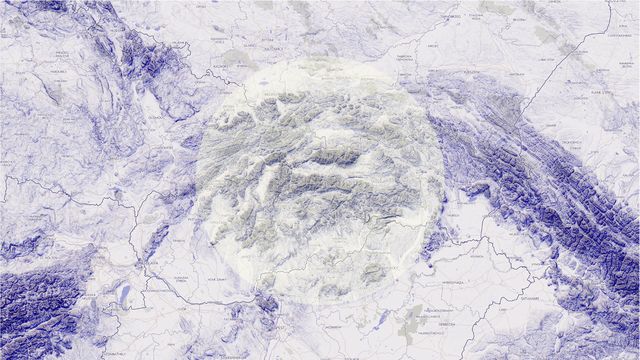

Though it was either ignored or claimed as an exception from the rule in the centre-of-gravity debate, Budapest’s blackmailing position has actually pointed to the complexity of Central (and East) European engagements. From the bird’s eye view, Europe’s position seemed united against the rest of the world. Zooming in, however, even the Eastern flank variedly split into north-eastern and south-eastern gradients: Czechia and Poland looking more to the north in favour of Ukraine, Slovakia being more reluctant and Orbán’s Hungary totally unsupportive.

The elections reaffirm this split. Thus, the domestic politics should be taken more seriously as a condition for foreign policymaking; otherwise there is a risk of legitimacy backlashes. Fico’s election strategy only mainstreamed the increasing societal reluctance to bear the costs of Russia’s war in Ukraine. Polish farmers ruined the carefully cultivated image of Poland and Ukraine’s unconditional security and economic friendship as the cornerstone of the East as a future centre of the EU/NATO decision-making.

President Zuzana Čaputová’s justification of the Slovak ban on Ukrainian agricultural imports as a “protection of Slovak interests” and her symbolic no to the public bilateral military aid are thus not necessarily twofaced. She responded to the so-far neglected engagement with the domestic public opinion. In contrast to his heated election rhetoric, the new Prime Minister Fico has been also taking a more cooperative approach to the delivery of the EU and private military support, dissenting only on the Slovak public military assistance.

Finally, Poland’s return might even increase the centre-of-gravity hopes of the country becoming an unconditionally pro-EU regional power. Due to (not only) the domestic politics, Tusk might, however, follow his campaign mindset. When reacting to the grain crisis, he called for a “tough, realistic [foreign] policy” that would primarily secure “Polish interests, but also help Ukraine”. Although the new government will remove the strain on the Brussels-Berlin-Warsaw line, Polish foreign policy cannot be expected to go through an idealized pro-EU and pro-West European turnaround.

Pluralist Central Europe

Against these developments, Czechia seems to be an island of stability. In 2023, the new President Petr Pavel entered office with a pro-Union/NATO and pro-Ukraine stance. The presidential elections made the Czech foreign policy more coherent given the liberal-conservative allegiances between the President and the governmental parties in power. The danger of slipping into triumphalism (along with or against Central European partners) should be, however, replaced with a more pluralist approach.

Behind this seeming foreign policy stability, Czech domestic politics is also complex. Despite the still high levels of pro-Ukrainian sentiments, a growing fatigue can be observed, including the declining support for military assistance. There is also a continuing disagreement over the issues of EU enlargement and reform inside the government, between the President and some governmental parties, and between the government and the opposition. In these circumstances, a pluralist consensus concern ing Ukraine, enlargement, and EU reforms is needed to solve these issues sustainably.

The tight societal relations with Slovakia do not justify Czech triumphalism either. This was exemplified by Pavel’s claim that Fico’s election as the new prime minister would, “to a certain degree, disrupted the relations between us”. The way forward seems to be Prime Minister Petr Fiala’s imperative that we “must be able to talk to each other” in spite of different views. This should be practiced in close bilateral relations or the Visegrád and Slavkov formats.

Poland should be also engaged with sober expectations and where the opportunities emerge. This can be done in the V4 format or broader EU like-minded coalitions. Czechia can be part of Poland’s return to the so-called EU mainstream, albeit this re turn will firstly engage more with Berlin, Paris, or Brussels. Poland’s voice in the former relations still needs to be grounded in having a credible weight in Europe’s center and east. Here, both states can be pillars of selected like-minded coalitions that represent shared, yet triumphalism-free voices on the EU reform and enlargement.

→ An effective Central European cooperation should abandon the language of political moralism inside the region and/or against European allies and understand the real internal differences as also an opportunity. This will allow for a more sustainable foreign policy cooperation.

→ The EU enlargement and reform will be new challenges for Central European states and their cooperation. A pragmatic and pluralist approach should be encouraged during negotiations of the (Central) European like-minded coalitions on both questions.