What can we expect from the 2023 presidential and parliamentary elections in Turkey?

paper

Turkey’s next presidential and parliamentary elections are scheduled for 18 June 2023. These elections constitute a critical juncture for Turkey’s future. They will either put an end to or consolidate the 20 years of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) rule in the country. Due to a worsening economic crisis and a deepening refugee question, the government policies have lost significant levels of public support in the last two years.

Yet, the elections in Turkey are held under unfair conditions due to the government control of the media, misuse of state resources and the vast powers that the executive has over the judicial authorities. The amendments introduced in the election law in April 2022 and the disinformation bill that passed in October 2022 create further advantages for the government in terms of increasing its control over the electoral process. Under these conditions, the success of the oppositional alliances depends on two criteria. First, the alliances must become unified in terms of supporting a joint candidate in the presidential elections both among and within themselves.

Second, they must spend extraordinary effort to mobilize the undecided and protest voters, which would give a strong message of their determination to win the elections. If the opposition wins the elections, there will be a new window of opportunity for the EU and the new Turkish administration to prepare the grounds for a positive, stable relationship. Yet, the EU should not expect a speedy recovery in the relations due to mixed stances within the opposition and the recurrent societal perceptions that ‘the EU is biased towards Turkey.’ If the current government is re-elected, the EU should prepare itself for an increased frequency of escalated political tensions with Turkey. The EU should aim to develop a new interest-based framework to cooperate with Turkey in the areas of trade, migration, border protection and energy.

THE CURRENT SITUATION AND THE POLLS

According to the latest polls conducted by agencies such as MetroPOLL, the distribution of votes among the opposition parties is as follows: The support for the secular social-democratic Republican People’s Party (CHP) ranges from 21 to 26 per cent, the corresponding figure for the pro-Kurdish People’s Democracy Party (HDP) ranges from 8 to 12 per cent and that for the nationalist Good Party (IYI) is between 11 and 15 per cent. There are also some minor religious-conservative parties, two of which – DEVA (“remedy”) and the Future Party (GP) – emerged as splinters of the AKP in early 2020. The support rates of these religious-conservative parties as well as the newly founded anti- refugee Victory Party (ZP) range from 1 to 2 per cent.

According to the same polls, the AKP has a support rate ranging from 26 to 32 per cent while that of its junior coalition partner, the nationalist MHP, ranges between 6 and 8 per cent. There is also a group of undecided voters, boycotters, and non-responders whose percentage ranges between 13 and 18 per cent.

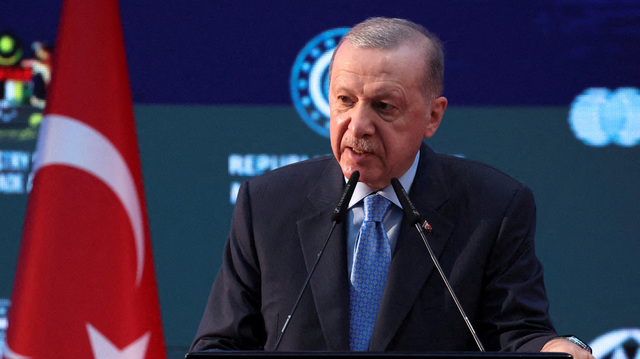

The opposition parties, including the CHP, the IYI and two minor conservative parties, the Democratic Party (DP) and the Felicity Party (SP), had established the Nation’s Alliance, which is a rival for the pro-government People’s Alliance, in 2018. Even though each party in the Nation’s Alliance had nominated their own presidential candidate in the first round of the 2018 presidential elections, they agreed to support one another’s candidates in the second round. Yet, they lost the race in the very first round after Recep Tayyip Erdoğan of the People’s Alliance won 52.6 per cent of the votes and was thus re-elected.

Compared to 2018, the Nation’s Alliance today also includes the AKP’s splinters, DEVA and the GP, and has a pledge to nominate a joint presidential candidate in the first round of elections. In this way, the six leaders of the alliance, often referred to as the Table of Six, aim to give a clearer image of unity and determination to win the elections in 2023. They have also made an agreement to build a strengthened parliamentary system once they come to power. They have described the current political situation as ‘Turkey’s deepest political and economic crisis,’ and a consequence of ‘the arbitrary and non-compliant administration that runs under a super-presidential system’.

Finally, the pro-Kurdish HDP has formed the Labor and Freedom Alliance with some minor socialist parties, including the Turkish Workers’ Party (TIP), which currently has four seats in the parliament. On par with the Table of Six, the HDP also supports the goal to build a strengthened parliamentary system in case of an oppositional victory.

According to the MAK poll agency, those who support the ruling People’s Alliance make up 40 per cent of all voters; the Nation’s Alliance, 43 per cent, and the Labor and Freedom Alliance, 10 per cent. As the other polls also suggest, there is surely a 4–5 per cent variation in these support rates. Yet, the numbers indicate that if the two oppositional alliances unite over a joint candidate and mobilize the undecided voters, they will have a chance to defeat the ruling People’s Alliance in the 2023 presidential elections.

POTENTIAL OUTCOMES OF THE 2023 ELECTIONS

The upcoming elections are comprised of both parliamentary and presidential elections, and it is possible to talk about four scenarios regarding how they will end.

- In the first scenario, the People’s Alliance will re-win the presidency and re-obtain a majority in the parliament, which is likely to sustain the current authoritarian dynamics.

- In the second scenario, an opposition coalition (i.e., the Table of Six supported by the Labor and Freedom Alliance) will win both the presidency and the parliamentary majority, which can start the process of building a strengthened parliamentary system and democratize the regime.

- In the third scenario, the People’s Alliance will win the presidency but lose the majority in the parliament. In this case, the current politics of Turkey under the leadership of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan is not likely to be affected much. Similarly to the first scenario, the president will continue to rule with vast executive powers, and use his authority to issue decrees and bypass legislation. In fact, Turkey’s new presidential system, adopted in a popular referendum in 2017, turned the Turkish parliament more or less into a shadow institution and gave supreme power to the president.

- In the fourth scenario, the opposition coalition will win the presidency but lose the parliamentary majority. In this case, the new president will have the power to implement institutional and economic reforms. The opposition’s commitment to return to a parliamentary system will be at stake since it needs parliamentary majority to make the necessary constitutional amendments (or to put them to a referendum). Yet, in this scenario, the elected AKP and MHP legislators will be deprived of their executive powers. Therefore, it is likely to witness collective party switchings from the AKP and the MHP in support of a new parliamentary system.

It is not likely that any party within the Table of Six or the Labor and Freedom Alliance will switch sides and join the ruling bloc prior to the elections. The IYI had earlier supported a pro-government candidate in the mayoral elections in an eastern province of Turkey due to its hardline stance on the Turkish-Kurdish conflict. But such a situation is not likely occur in the presidential elections since their party identity is strongly based on anti-AKP sentiments.

All in all, the possibility of a transition to parliamentary democracy depends first and foremost on whether there will be an oppositional victory in the presidential elections (the 2nd or 4th scenario). Winning a majority in parliament together with the presidency will make the opposition’s job easier but even if it fails to gain a parliamentary majority, it has the chance to build a new system. The current presidential system, deprived of checks and balances, will endure for a certain period of time and the transition will require the good faith of the new president and his/her commitment to his/her pre-electoral promises. Finally, in all four scenarios, it is possible to expect post-electoral violence if the claimed victory (of either the pro-government or the opposition alliances) is based on a small margin like 2–3 per cent. The AKP has been in power for 20 years.

WHAT ARE THE CHANCES OF THE OPPOSITION WINNING THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS?

The opposition’s chance of victory in the upcoming elections is dependent on two criteria. First, there is the need for a compromise both within and across the oppositional alliances in terms of choosing a joint presidential candidate. This requires the parties to downgrade their ideological and opportunistic disagreements with one another. Second, the parties need to mobilize the undecided voters and boycotters by demonstrating their unity and determination to win the elections.

A presidential candidate nominated by the Table of Six cannot be successful alone and requires the support of the Labor and Freedom Alliance. The Turkish-Kurdish conflict remains the main barrier against such a compromise since this issue is highly securitized by the pro-government actors. Representatives of the pro-Kurdish HDP are criminalized for allegedly having ties with the outlawed Kurdistan Workers Party (PKK) while the HDP itself faces a possible closure decision of the Constitutional Court. Besides this, the IYI is under no circumstances eager to engage in talks with the HDP or share any government posts with it due to its staunch Turkish-nationalist position.

There are also opportunistic rivalries within the alliances. Most importantly, within the Table of Six, the CHP chairman, Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, perceives his party to have the main leverage on the candidate selection process, as it is the largest party at the Table. He has publicly stated that he is ready for a presidential candidacy if the Table of Six agrees with it. Besides this, Erdoğan himself challenged Kılıçdaroğlu and made a call to him where he asked him to be his rival in the presidential contest. However, the IYI chair, Meral Akşener, reminds others that the CHP is bound by the negotiations and that the joint candidate should be “someone who can win” against Erdoğan. This implies that her party prefers a candidate other than Kılıçdaroğlu. There are also signals that the CHP party organization is having factional rivalries over the question of the party’s presidential candidate. In addition to the chairman Kılıçdaroğlu, the party has two more popular figures, the mayor of Istanbul, Ekrem Imamoğlu, and the mayor of Ankara, Mansur Yavaş, who are also potential candidates for the presidency. There are speculations that the party is divided as to which of these three names to support.

Is there a way out for the opposition in the light of such ideological and opportunistic rivalries? Regarding the ideological Turkish-Kurdish conflict, there is one way out. It is indeed not possible to resolve the 40-year-long conflict in a timespan of seven months. But in a not-too-distant past, the HDP’s decision to externally support the joint candidate of the CHP-IYI alliance, Ekrem Imamoğlu, in the Istanbul mayoral elections had paved the way for an oppositional victory. The HDP supported İmamoğlu because he was nominated by the CHP (not by the IYI) and had embraced an inclusionary language that did not discriminate against HDP supporters. Such a scenario is more difficult to attain in the presidential elections but is not impossible. In case the CHP succeeds in overcoming its own intraparty conflicts, it can act as a midway party between the Table of Six and the Labor and Freedom Alliance during the negotiations. With regard to the resolution of opportunistic conflicts among the members of the Table of Six, the IYI chair, Akşener, has taken up the role of a facilitator since she declares no ambitions to be the next president and points to the need for a compromise in finding the joint candidate.

HOW TO MOBILIZE?

Having a joint candidate for the presidency is a necessary but not sufficient condition for the opposition to win the elections due to the potentials for fraudulence and unfair conditions of competition, which were already noted by international observers in the 2018 presidential elections. The opposition needs to create a level of mobilization beyond what would normally be observed in cases of victories in democratic regimes. A strong commitment to winning, effective governance and a return to economic normalcy are messages that need to be clearly communicated through all possible channels to attract undecided voters and boycotters. The collaboration with voluntary groups to convey such messages, register voters, get them to vote, and monitor the ballots and vote counting processes is an important component of such a mobilization, and is needed for an incumbent turnover in hybrid regimes similar to Turkey. Such a mobilization can be led both by the opposition’s joint candidate and via the joint efforts of grassroots party activists.

All in all, in order to be successful in the upcoming elections, the opposition parties across and within the existing alliances must, first, find a way out of the ideological and opportunistic conflicts to nominate a joint presidential candidate and, second, pursue an extraordinary effort to mobilize the masses around this joint candidate.

WHAT ARE THE CHANCES OF THE GOVERNMENT COALITION WINNING THE PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS?

There has been a diminishing support for the AKP-MHP coalition in the last two years thanks to the economic collapse that tremendously raised the costs of living, and the influx of Syrian refugees that escalated people’s anger against the government. However, having the majority of seats in the parliament, the ruling bloc also makes maneuvers to change the tide in its favor. The amendments to the electoral law in April 2022 and the disinformation bill that passed in October 2022 were the most important ones. The new electoral system disadvantages the minor religious-conservative parties in the opposition alliance, forcing them to give up their own party banner and nominate their candidates through the lists of larger parties in parliamentary election.

In compliance with the new presidential system’ of Turkey, it also makes the president exempt from rules that prohibit Ministers and members of the parliament from using state resources while on campaign tours. The disinformation bill, on the other hand, introduces a prison sentence of one to three years for those who ‘disseminate false information about the internal and external security, public order and general wellbeing of the country in order to create anxiety, fear or panic among the public’. Tightening government control over social media, the bill has the potential to undermine the parties’ equal rights to issue propaganda during their campaigns and to independent reporting on the election day.

At the domestic level, the emergence of a new anti-refugee party, the ZP, also created an advantage for the ruling coalition. Accusing not only the government policies but also the opposition itself of being incompetent, the ZP has a support rate of about 1–2 per cent. It takes votes mainly from the main opposition party CHP and benefits the People’s Alliance. There are also international developments that came in handy for the government, as they strengthened its legitimacy claims regarding the continuance of its power. The current foreign policy orientation of Turkey should not be separated from the anxiety that the upcoming elections create in the government. The current government’s ‘balancing act’ regarding the Russian-Ukrainian conflict goes hand in hand with a discourse underlining the need for a strong leader. Having a strong leader like Erdoğan is portrayed as what is needed to protect Turkey’s national interests and restore its glory.

Turkey also increased its bargaining power vis-à-vis the Western powers – most recently threatening to block Finland and Sweden’s NATO bid, but it lifted its veto in exchange for pledges on counterterrorism and arms exports. It also showed an intention to become a member of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO) and signed ‘historic deals’ with Ukraine and Russia on the creation of a food corridor. All these acts provide an image of competence in times of conflict in contrast to the image of an uncertain future under a currently unknown oppositional leader. Indeed, the latest polls from September indicate a steady increase in the job approval rate for Erdoğan, compared to August 2022. Hence, Erdoğan’s re-election chances remain intact. He may well be re-elected unless the opposition creates a strong mobilizational force around a joint presidential candidate.

CAN THE OPPOSITION ESTABLISH A STABLE GOVERNMENT IF IT WINS THE PRESIDENCY?

The Table of Six has established commissions that negotiate reforms in the most fundamental policy areas of Turkey. These areas include public administration, law and justice, fighting corruption, employment, social policy, education, science & technology, foreign policy and security. In order to implement the policies, the Table of Six prioritizes a public administration reform, discussing the need to establish oversight mechanisms over public expenditures, and make the Budget Law subject to strong parliamentary scrutiny and the Turkish Court of Accounts independent from government pressure

Each party at the Table of Six has its own agenda regarding the way out of the economic crisis and the refugee problem but so far there has been no joint declaration on these issues. The country needs long-term structural reforms, which include giving the Central Bank its independence back, and fighting against nepotism and corruption, and each party leader individually refers to these points in oppositional media outlets. On the other hand, the anti-immigrant sentiment in Turkey has reached a ‘tipping point’ and even the main opposition leader, Kılıçdaroğlu, makes populist promises about his party’s determination to send Syrians back home The Table of Six has established a Commission on Immigration and Asylum Seekers that aims to discuss the solution to the refugee problem and prevention of irregular migration to Turkey; however, it is reported that the leaders have deep disagreements on how to resolve this issue

If the parties of the Table of Six agree on a joint roadmap to tackle these problems prior to the elections, the chances for a stable government will be higher. On the other hand, we do not know whether the Table of Six and the Labor and Freedom Alliance will be able to work together to improve the human rights situation in Turkey. The problems pertaining to Kurdish rights and, most importantly, the release of the HDP co-chair Selahattin Demirtaş from prison, are a priority issue for the Labor and Freedom Alliance

HOW WILL TURKISH FOREIGN POLICY CHANGE AFTER THE 2023 PRESIDENTIAL ELECTIONS?

If the elections introduce a new Turkish administration, it is possible to expect a shift in Turkey’s foreign policy toward a more pro-Western orientation. This, however, does not mean that there will be a speedy recovery in the relations between Turkey and the West. Euroscepticism and anti-Americanism continue to shape Turkish public opinion to a large extent. The main opposition party CHP sees Turkey’s place as being in the Western camp while the IYI and the HDP have more mixed or moderate views on this issue.

The current relationship between the Turkish government and the EU is built on a pragmatic cooperation in areas of common interest, especially migration, security and energy, but political conflicts frequently intrude on this cooperation. The trust between Turkey and the EU has been low: while Turkey has no belief that the EU would deliver on its promises, the EU is often torn internally as to how to react against Turkey’s assertive shifts in foreign policy. The AKP government does not hesitate to improve its relations with countries like Russia, Iran and China while it takes unilateral diplomatic and military initiatives when its interests diverge from those of the EU and NATO

According to a recent poll, the support rate for Turkey’s membership in the EU is around 50 per cent, while those who are against it make up 40 per cent of the population. The strongest backing for the EU membership comes from voters of the HDP (71 per cent) and the DEVA (72 per cent). Most of the CHP voters are also in favor of Turkey’s EU bid (67.5 per cent) while only 44 per cent of the IYI voters support it. All in all, the average support for the EU membership among the voters of the opposition parties is higher than the average support for it by AKP (38 per cent) and MHP voters (47 per cent). On the other hand, the perception that the EU is biased against Turkey is very high among the supporters of all parties. The same poll finds that the proportion of those who think Turkey should prioritize the EU and the US over Russia and China is 39.3 per cent while the percentage of those who think it should prioritize Russia and China over the EU and the US is 29.5 per cent.

Most importantly, over half of the Turkish society sees the US as the biggest threat to Turkey, and Russia follows the US in this respect with only 19 per cent of the respondents holding this view. With this picture in mind, it is important to note how the foreign policy visions of the opposition (i.e., the CHP, the IYI, and the HDP) and the government differ. The leadership of the main opposition party, the CHP, is highly critical of the AKP’s assertive foreign policy. If Turkey had to choose between the two camps, the EU and the US vs. Russia and China, it would have to choose the former because this choice today represents a choice between democracy and autocracy; and Turkey must be on the side of democracy.

As a response to Erdogan’s latest statements on the possible membership in the Shanghai Cooperation Organization (SCO), the CHP argues that there is no harm in Turkey developing its relations with regional and international organizations at a global level but the SCO can never be an alternative to NATO or the EU The CHP program further highlights that the Turkish- Greek disputes should be resolved through a dialogue and respect for mutual interests. However, the CHP chairman, Kılıçdaroğlu, from time to time does not hesitate to make nationalistic statements questioning Erdoğan’s ‘true patriotism’ in the media, reminding the Greek administration of the nationalist tradition of Turkey and saying that it has no tolerance for the militarization of the islands

The IYI, coming from a pan-Turkist tradition, is genuinely interested in developing ties with the Turkic population in Central Asia and beyond. It does not support Turkey’s full membership in the EU but emphasizes the need for a ‘healthy’ relationship that would serve their mutual interests. It aims to work in good faith to resolve the territorial problems with Greece through dialogue and negotiations and stands in contrast to the hard-liner position of the MHP in government. The IYI also has suspicious feelings toward Russia and China, especially since the awareness of the Uyghur genocide has become widespread. The IYI puts the full blame on the Putin administration for its violating of international law and the sovereignty rights of Ukraine and posing a threat to the security and territorial integrity of other countries in the region

The HDP, on the other hand, is a staunch supporter of Turkey’s integration into the EU, which it sees as a safeguard for the recognition of Kurdish rights in Turkey. Due to its socialist orientation, however, it paradoxically simultaneously advocates anti-Westernism and is critical of the ‘capitalist imperialist system’ that has been supposedly created by the West ‘to dominate the world’. With regard to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict, the party leadership puts equal blame on ‘the expansionist policies of NATO and Russia, which ignored the will of the people’.

All in all, the opposition parties are eager to give more attention to diplomacy, negotiations, and cultivating ‘healthier’ relations with the EU than is currently being given. However, it is difficult to expect a smooth amelioration in the EU-Turkey relations due to the mixed, and oftentimes nationalistic, stances within the opposition and the societal perceptions regarding the EU’s biased approach towards Turkey.

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR THE EU

The recommendations provided below are mainly for what position the EU should take under different election scenarios. The Czech Republic should support the EU position under these scenarios.

In case the opposition comes to power, there will be a window of opportunity for the EU to intensify its dialogue with Turkey on a range of issues and on different levels. But each side needs to take lessons from the past and discuss ways to rebuild their mutual trust. In this case, the recommendations for the EU can be summarized as follows:

→ If the new Turkish administration shows a political will to resume Turkey’s internal reforms and improve its alignment with European policies, the EU should consider resuming certain aspects of the EU-Turkey relations that are currently blocked at the level of the European Council. Some examples of such aspects are the EU-Turkey Association Council meetings, the technical committees’ meetings and the opening of additional chapters of the accession negotiations.

→ The EU should actively support Turkey in its effort to recover from the economic crisis and restore its parliamentary democracy. The EU should consider, e.g., increasing its support allocated to Turkey via the IPA funding.

→ The EU and Turkey should intensify their dialogue on migration, border protection, and fighting against smugglers. The Czech Republic should encourage a discussion on the future of European support to refugees in Turkey.

→ The EU and Turkey should resume their dialogue on the current implementation and possible modernization of the Customs Union, which came to a halt due to the political developments and the currency crisis in Turkey in 2018.

→ The EU should enhance the P2P contacts and consider a visa facilitation for Turkish citizens (primarily students) in the short term. It should offer technical help for dealing with the remaining visa facilitation benchmarks. A visa liberalization should follow in the long term in case Turkey shows a higher convergence with the EU.

→ The EU should encourage a subregional political dialogue among Greece and Turkey as well as the Turkish and Greek Cypriots. The tense relations between Turkey and its neighbors have a negative impact on regional stability prospects, and the EU-Turkey relations.

In case of a re-election of the current government, the pragmatism in the EU-Turkey relations will continue. In this scenario Turkey’s alignment with the EU policies is likely to remain low and the accession process will probably remain frozen. In this case:

→ The EU should strive to keep the channels of communication with Turkey open.

→ The EU should pay attention to forming an alternative, interest-based framework for its relations with Turkey. Within this framework, Turkey can continue to be an important partner in economic and trade relations and a strategic country to cooperate with in the shared neighborhoods regarding the areas of migration, border protection and energy.

→ The EU should be ready for an escalation and a greater frequency of the political tensions with Turkey. It should continue to promote informal consultations with Turkey and the parties involved in the disputes. Such consultations can be initiated on an ad-hoc basis but can be integrated into the new interest-based framework in the long run.