The Current State of EU-Turkey Relations and Implications for Czech Foreign Policy

paper

The Czech Republic should approach the EU-Turkey relationship from the perspective of how to bring back the EU’s democratizing influence over Turkey because the decline of democracy in the country is conducive to its unilateral and disruptive foreign policy in areas that are of strategic importance to the EU. The EU has recently adopted a global human rights sanctions regime that targets autocratizing regimes responsible for human rights violations, which can potentially include Turkey. Yet, some softer mechanisms contributing to democratization, such as the strengthening of the linkage between autonomous civil society organizations (CSOs) in Turkey and their European counterparts, are also worth considering as a foreign policy tool. The Czech Republic’s concern about the decline of democracy and rule of law worldwide makes it ideal that its foreign policy should employ such a soft strategy toward Turkey. It can motivate its own CSOs to increase their linkages with the CSOs that have managed to remain autonomous within Turkey’s polarized domestic setting. To this end, the Czech Ministry of Foreign Affairs can consider including Turkey as one of the priority countries in its Transition Promotion Program. The potential transnational cooperation between the Czech CSOs and the autonomous CSOs in Turkey can focus on less controversial issues for Turkey that still, however, constitute urgent challenges for both the Czech Republic and Turkey. Immigration and climate change are two such exemplary issues.

Introduction

The question of Turkey was once a question of how to define European identity for the European Union. Turkey’s candidacy to the EU was challenging the self-perception of Europe as a multicultural space. In the last decade though, the EU-Turkey relationship evolved toward a strategic partnership at the expense of the EU membership conditionality. The 2015 refugee crisis reinforced this process when the so-called EU-Turkey ‘refugee deal’ was signed in 2016. Turkey was offered benefits in exchange for its cooperation with the EU and became the EU’s key strategic partner by helping to secure its external borders against refugee flows.

The tensions in this strategic relationship escalated with the outbreak of the Eastern Mediterranean crisis. The EU called on Turkey to stop its ‘unilateral’ and ‘provocative’ drilling activities in the region, and showed its full solidarity with Greece and Cyprus while insisting that Ankara engage in a ‘peaceful dialogue’ with its neighbors. The Turkish government, on the other hand, demanded the impartiality of the EU as the first step to starting a ‘sincere dialogue,’ and drew a historical continuity between the past and present position of the EU in the sense of its being ‘unfair and disproportionate’ toward Turkey. Later, in October 2020, the EU Council slightly softened its approach toward the country by presenting potential avenues of cooperation such as the modernization of the Customs Union, visa liberalization and cooperation on the refugee problem as prospects for the establishment of an effective cooperation. Yet, in December 2020, the conclusions of the Council included a re-condemnation of Turkey’s unilateral steps in the region as well as an agreement on economic sanctions. Meanwhile the Turkish government found these conclusions biased and made it clear that it will not give up on its claims.

These developments demonstrate that the EU’s leverage over Turkey as a candidate country has significantly weakened. One reason emanates from the way Turkey’s accession process to the EU was frozen. The EU’s reluctance to play a more active role in resolving the Cyprus question was perceived as unfair by the Turkish public once a UN-backed federal solution aiming to reunite the island was vetoed by the Greek Cypriots but supported by the Turkish Cypriots in 2004. The accession negotiations with Turkey could not continue due to the resilience of the Cyprus conflict. On the other hand, during the negotiations between 1999 and 2005, the public debates pronouncing Turkey’s cultural differences from the EU member-states raised skepticism in the Turkish society regarding the EU’s sincerity in accepting Turkey as a member.

The second, broader reason for the EU’s fading leverage over Turkey falls into the global wave of autocratization. Following the EU foreign policy’s failures to cope with the Middle Eastern and Ukrainian crises on one hand, and the ineffective measures that were taken to deal with the Eurozone and refugee crises on the other, the EU’s democratic influence has declined in its periphery in general. Non-Western powers like Russia and China provide exit routes to political groups and governments that defect from the EU through various trade and investment opportunities to reduce their costs of defection. This includes Turkey.

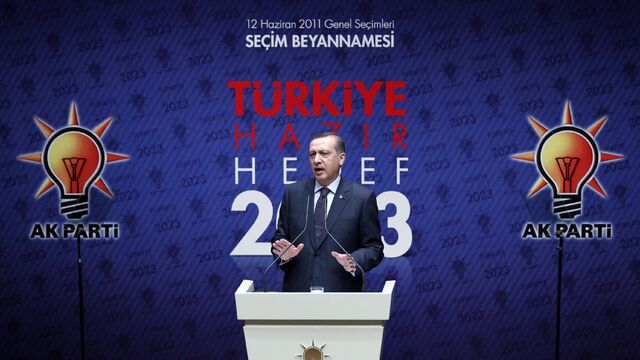

The Turkish government incites popular nationalism among its supporters, referring to the ‘hypocritical’ approach the EU has taken against the country. It has reinforced its plebiscitary ties with its supporters (i.e. through referendums) and weakened the rule of law and institutions of horizontal accountability.1This process is constitutive of a foreign policy where ‘Turkey does not bow down in front of the West’. Individual politicians exert too much influence on foreign policy decision-making and bypass the bureaucracies that are relevant to this process. Hence, while Turkey’s unilateral acts – often including a strong military component in the East-Med (as well as in Libya, Syria and the Caucasus) – are condemned by the EU, they are considered highly legitimate in the eyes of the government supporters at the domestic level. Given these developments, how to restore a working EU-Turkey relationship is a question that is more complex than ever and the tools to cope with it should fall into the framework of reversing the global wave of autocratization.

Linkage: Another tool to combat autocratization?

On 7 December 2020, the EU agreed on a regulation establishing a global human rights sanctions regime. This regulation paves the way for the EU to use a broad range of policies, tools, and political and financial instruments as a mechanism of leverage over state and non-state actors who are “responsible for, involved in or associated with serious human rights violations and abuses worldwide”. While the critics are skeptical about whether this regime can bring a major upgrade in the EU human rights and democracy policies, it can also take a long time for the EU to utilize this tool in coping with Turkey. The efforts to take punitive action against Turkey often divide the member-states and this dilutes the very effectiveness of these efforts.

Yet, leverage is not the only way to deal with autocratizing states. Linkage to the EU, defined as the density of a country’s economic, political, organizational, social, and communication ties to the European Union, is known as an influential mechanism that promotes democratic norms in a more diffuse and subtle way. Linkage encompasses myriad networks of relationships that connect individual polities and societies to Western democratic communities. It expands the number of domestic actors with a stake in their country’s international standing. When the linkage to the democratic political systems is extensive, the societal actors in autocratizing states can act more autonomously, as they are ready to renounce the policies and decisions of their government when they deem it necessary.

The question is, can linkage be an option for Turkey today? Some argue that once the membership conditionality is no longer on a country’s agenda, it loses its effect on the country’s democratization. Indeed, the linkage between Turkey and the EU had a positive effect on Turkey’s democratization before the failure of the negotiation talks. Between the years 1999 and 2005, Europe was a reference point not only for governance-related reforms, but also for societal actors voicing their visions of political change and modernization in the country.

Today, Turkey’s linkage to the EU continues through its official candidacy status. It has been one of the largest recipients of the European Instrument for Democracy and Human Rights (EIDHR). The Instrument for Pre-accession Assistance (IPA) also established an ongoing EU-Turkey Civil Society Dialogue. The large funds allocated to Turkey through these instruments aim to ensure the active participation of civil society in public debates there, including that on democracy, human rights and the rule of law. Yet, the evidence shows that the growing polarization made the autonomous CSOs in Turkey increasingly fragmented and weak while it encouraged the rise of the pro-government CSOs due to their dependency on the government, which controls the distribution of the EU funds.

Hence, the linkage to the EU through the existing funds and instruments does not necessarily bring a diverse and active civil society with an ability to change or even influence the government policies. There is a need to sustain the resilience of autonomous CSOs in Turkey. Promoting their existence and operation in the transnational civic space can make them remain resistant against the autocratization trend in the country. Transnational civil society linkage, if it is to become a foreign policy tool for democratization, must pay attention to the establishment of cooperation with domestic civil society actors that have managed to remain autonomous through their ability to openly oppose the government policies in their areas of expertise. On the other hand, cooperation in politically less controversial issues has the potential to avoid the polarizing strategy of the Turkish government. The CSOs that work in the areas of human rights monitoring, minority rights, peace and reconciliation, for instance, are usually perceived as ‘politically motivated’ by the Turkish government. The areas of transnational cooperation with the autonomous CSOs can focus on different priorities for different EU member-states. The section below suggests immigration and climate change as two potential areas of cooperation with the Turkish autonomous CSOs for the Czech Republic.

Can the Czech Republic improve its transnational linkage with Turkey?

As a legacy of its first post-communist president, Václav Havel, the Czech Republic has taken pride in supporting democracy and human rights in various nondemocratic states throughout the world. Under the auspices of the “Transition Promotion Program”, for instance, it pays attention to promoting democracy and human rights in countries that are close to the Czech Republic in cultural, historic, geographic or other terms.

Due to the scarcity of historical and cultural ties to Turkey, the Czech Republic does not have such a transnational linkage to it. Moreover, it rarely takes part in the partnerships included in the EU-Turkey Civil Society Dialogue. The two countries have sustainable trade relations and mainly cooperate in the area of energy. On the other side, since it became a member of the EU, the Czech Republic has officially supported Turkey’s membership to the EU, arguing that the integration process will naturally bring democracy and rule of law to any candidate country, even though the public opinion was less in favor of this position. As democracy started declining in Turkey, the Czech Republic followed the official EU stance. The minister of foreign affairs, Tomáš Petříček, stated that the deterioration of the rule of law, democracy and human rights in the country created obstacles against any advancement in EU-Turkey negotiations and therefore the focus is no longer on the accession of Turkey, but on the countries of the Western Balkans. The Czech Republic’s official position in the Euro-Med crisis was also in support of the EU official position and in solidarity with Greece: the minister of foreign affairs agreed that the EU ‘should be prepared with a possible list of sanctions in case Turkey does not end its unilateral actions and does not do everything it can to de-escalate the tension’.

While the statements in support of the official EU position against Turkey are reasonable for the Czech Republic, their effect on political change is limited as the Czech Republic is a member-state that does not belong to the heart of the decision-making process in the EU. If the Czech Republic cares about democracy and stability at the EU borders, it is in its best interest to formulate a refreshing approach toward Turkey and go beyond joining the majority of the member states for leverage.

The Czech Republic can consider including Turkey as a priority country in its democracy promotion instrument, the “Transition Promotion Program.” To this end, the almost non-existing transnational civil society linkage between the Czech Republic and Turkey can be improved in the aforementioned way. The civil society in the Czech Republic can be motivated to establish cooperation with the autonomous CSOs in Turkey. Considering that issues like immigration and climate change constitute urgent challenges for both the Czech Republic and Turkey, the CSOs in the two countries can build transnational partnerships in these areas. The autonomous CSOs in Turkey, which are critical of the government policies yet cannot operate effectively due to their lack of access to the government-controlled funds, can be prioritized in building these partnerships.

Immigration: A potential area for the Czech-Turkish transnational cooperation

The EU Facility for Refugees in Turkey aims to improve the humanitarian and socio-economic situation of Syrian refugees and their integration in Turkey. There are over 3.5 million Syrian refugees in the Turkish territory, which makes this community the largest of all Syrian refugee communities worldwide. The Facility has so far pledged a significant amount of European funds to Turkey and more will follow. The refugees need support in rebuilding their futures as well as maintaining their access to education and the labor market. Such goals are particularly challenging in the economic recession that Turkey is facing under the pandemic. Sharing equal responsibility with the stakeholders in Turkey at the European level can help reduce the vulnerabilities of this community while contributing to the resilience of the autonomous Turkish NGOs that focus on this goal.

The Czech Republic framed its strategy to deal with the refugee crisis in 2015-2016 mainly from a national security perspective, which was extensively criticized by the human rights groups in the country. It will thus be in its interest to play a more constructive role on the ground within Turkey. This can be achieved through improving the transnational linkage between the Czech and Turkish autonomous CSOs that work on the Syrian refugee problem. Especially the Turkish CSOs desiring better immigration policies from the Turkish government and those that cross-examine the allocation of the EU funds can be traced and targeted for building such partnerships.

Climate change: another potential area for transnational cooperation

Located in the eastern Mediterranean, Turkey is one of the countries in the highest risk group regarding the adverse impacts of climate change in Turkey. It suffers from frequent forest fires and long periods of drought. The rapid economic and population growth in the country has contributed to massive ecological degradation in the last two decades. In its latest report on Turkey, the European Commission emphasized the need for Turkey to complete its alignment with the EU acquis on climate action and ratify the Paris Agreement. It also pushed Turkey to implement public participation and the right to access environmental information.

In the 2000s, the salience of environmental issues had increased and fostered great civic engagement. Yet today, the evidence suggests that the environmental CSOs have fallen prey to the intensifying polarization that characterizes Turkish society, with the government identifying many ecological groups as only interested in mobilizing the opposition and intentionally downplaying the country’s progress in environmental issues. In this regard, it is extremely important to identify and build linkages with the CSOs that have managed to remain non-partisan and autonomous. The transnational partnerships should be built with attention to the concerns of the environmental CSOs with the professional goal of implementing more and better climate-related projects in Turkey. The Czech Republic is a contributor to both the EU structural funds (by virtue of being a member-state) and global funds (as an individual donor) while Turkey is a recipient as a result of being a high-risk country for climate change.2 Hence, facilitating transnational networking among non-governmental sectors in the Czech Republic and Turkey can increase the absorption capacity for climate financing in Turkey.

Summary and policy recommendations

The EU-Turkey relations should be approached from the perspective of how to bring back the democratic influence of the EU over Turkey. Promoting linkage with the autonomous CSOs in Turkey in less controversial areas can provide a transnational civic space for them, making them remain resilient against polarization and autocratization in the country. As a country that shows concerns for the decline of democracy and rule of law, the Czech Republic can motivate its CSOs to establish such novel forms of transnational linkage with Turkey as follows:

The Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MFA) can include Turkey in its Transition Promotion Program to promote the linkage between the Czech CSOs and the autonomous CSOs in Turkey.

In so doing, the MFA can work with country experts and run a feasibility study to explore the government-dependent and autonomous CSOs operating in Turkey.

The MFA can further work with the Ministry of Environment and the Ministry of Interior to explore the specifics of potential partnerships between the Czech CSOs and the relevant Turkish CSOs. The areas regarding immigrant integration and climate change can be considered as two potential areas of transnational cooperation.