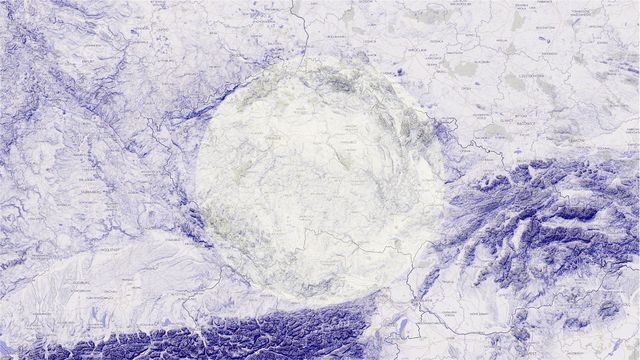

Does Central Europe Want The Western Balkans In The European Union?

The Russian aggression in Ukraine caused a new momentum for the discussions about European integration. As Ukraine gained EU membership status, questions about the membership of Western Balkans countries emerged. Asya Metodieva has devoted her chapter to these issues.

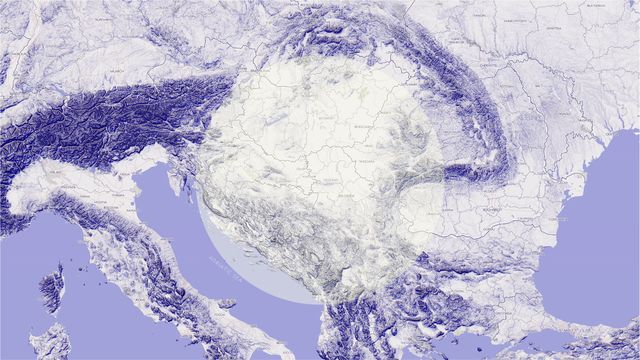

The EU accession of the Western Balkans (WB) has gained a new momentum following Russia’s aggression and the granting of EU membership candidate status to Ukraine. The idea of accelerating the process in favor of the WB countries plus Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia has been a part of the political discussions concerned with the need for the EU to reaffirm its geopolitical role in the new situation. Though it does not

replace the enlargement process, the European Political Community appeared as a new platform that creates more space for cooperation with the WB countries.

The Central European countries have consistently expressed support for the EU integration of the Western Balkans, yet there is much to be done. The Czech EU Presidency has achieved some progress on long-lasting issues but failed to engage the region so that the countries would have a more unified voice regarding the accession process. The question is whether formats like the Visegrád Group (V4) can play a meaningful

role, since the war in Ukraine has dealt a blow to the platform. Alternatively, other Central European formats can offer concrete forms of support for the WB.

Czechia and other like-minded Central European countries should cooperate on reviving or creating value-based regional formats that could push the integration of the WB as a shared foreign policy priority. To do so, governments across the region should consider joint diplomatic interventions that would help with bilateral and internal issues such as the dispute between Kosovo and Serbia, or that between North Macedonia and Bulgaria, as well as reforms in BiH.

THE WESTERN BALKANS CAN RELY ON VARIOUS FORMATS IN CENTRAL EUROPE, WHILE THE V4 SHOWS ITS LIMITS

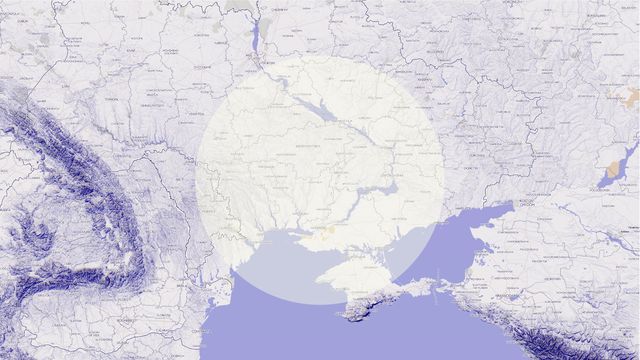

Given its stated ambitions and the history of its approach to the region, the V4 was supposed to be a player in the renewed discussion about the EU integration of the Western Balkans. The reality is different, though. The war in Ukraine and the sanctions against Russia create cleavages in the V4, leading Czech, Slovak and Polish politicians to increasingly distance themselves from the group (see the chapter by D. Šitera and J. Eberle).

The dividing line, namely Hungary’s controversial stance on Russia’s war and the EU’s response to it, prevents a more pro-active joint position regarding the inclusion of the WB into the new enlargement group together with Ukraine. Moreover, Hungary approaches the WB through its self-serving political friendships, polarisation campaigns, and business ties. For these reasons, there are now only limited chances for a V4 cooperation on foreign policy, including the question of the integration of the WB into the EU.

This weakens the position of the V4, but strengthens the opportunities for other formats, such as the Austerlitz (Slavkov), the Central European Initiative (CEI), the Three Seas Initiative, or the Central European Defence Cooperation (CEDC), among others.If there is a political will for it, nothing stops Czechia, Slovakia, and Poland, among other countries in Central Europe, from creating new or utilizing existing formats and working together on how to support the WB on the European path. For instance, the Austerlitz (Slavkov) – an informal cooperation of Czechia, Slovakia, and Austria – can be a platform where political and diplomatic support for the WB is solidified.

THE WESTERN BALKANS: A PRIORITY ON THE CZECH EU PRESIDENCY’S AGENDA?

Czechia has repeatedly expressed its commitment to the integration of the WB into the EU. Yet, domestic and international political limits could possibly explain why Prague was not more assertive in utilizing regional formats that would boost the support for the WB while holding the EU Presidency.5 The major external factor, the war in Ukraine, has brought more pressing issues than the enlargement: the energy crisis, inflation, and the refugee crisis.

The EU-Western Balkans Summit, which was the first such summit to be held in the WB, namely in Tirana, was meant to reconfirm the commitment to the integration of the region. While the acceleration of the enlargement process was not high on the agenda, the Presidency ended with concrete achievements. The EU leaders agreed on granting candidate status to Bosnia and Herzegovina, a visa liberalisation with Kosovo, and opening accession talks with North Macedonia and Albania. These were long-lasting issues in the relations between the EU and the WB.

The enlargement discussion became more present following the launch of the European Political Community (EPC) in October. While the EPC appeared as a response to the war in Ukraine, it also promises to be a new space where the voices of the WB countries can be better heard. The EPC is a format that recognizes the geopolitical shifts in Europe and provides an opportunity for a strategic dialogue and alignment between the participating countries. Yet, the EPC evokes both hope and concern among the WB countries.

The hope is that leaders of non-EU countries sitting around the table will be able to participate in the big discussions concerning the future of Europe. The EPC allows for the inclusion of the WB into a strategic dialogue and facilitates energy and security cooperation. Overall, the EPC opens space for a political consensus concerning the ongoing crises and risks related to the war in Ukraine, including political instability across Europe, inflation, and energy dependence. The EPC further increases the chances for dealing with bilateral relations on a personal basis through agreements between leaders.

The concern, however, is that the new format may slow down the enlargement efforts: since the EPC intends to bring non-EU countries to a closer cooperation with the EU, it risks being treated as a substitute for EU membership, thereby discouraging a full-blown enlargement. Such a development may cement the current stabilitocracies in the WB or inspire a new form of a ‘geopolitics first’ approach. Also, broader doubts about the viability of the EPC’s ‘Wider Europe’ concept remain, with some fearing that creating yet another format only contributes to more discussions without actual policy making.

CZECHIA’S SUPPORT FOR THE WESTERN BALKANS AFTER THE PRESIDENCY

For Czechia, having the EPC born in Prague was a chance to take a more vocal position on the future of Europe and the role of the EU enlargement process in it. Czechia can prioritise the integration of the WB after the end of the Presidency by taking initiative in regional formats that can make the support for the WB tangible. Becoming more pro-active in engaging with bilateral disputes in the WB should not be seen solely as a question of bilateral foreign policy, but also as one of overall European security. The achievements of the EU Presidency put Czechia in a position to encourage a cooperation among Central European countries that can provide mediation on issues blocking the accession process, such as the disputes between Bulgaria and North Macedonia, and Kosovo and Serbia, as well as the institutional crisis in BiH. Progress on either of these issues is not an easy task, especially in times of war in Europe. However, Czechia has already been able to take a stance on some of these issues and thus can strengthen its foreign policy cooperation with its neighbours who are willing to commit to a value-based approach to the WB.

→ The V4 has alternatives if the Central European countries are willing to be more proactive in supporting the WB. The question of enlargement can be pushed through functioning regional formats that exclude blockers such as Hungary and include countries like Croatia and Slovenia that are historically linked to the WB.

→ The Czech EU Presidency and the launch of the EPC in Prague raise expectations that Central Europe can be more active in mediating contested issues in the WB. Three key priorities for the region should be

to encourage a long-term normalization agreement between Kosovo and Serbia; reforms in BiH following its gaining of the EU candidacy status; and solving the dispute between North Macedonia and Bulgaria.

The chapter was published in this year's annual publication "Svět v proměnách 2023: Analýzy ÚMV".