More Continuity Than Change: Poland’s Foreign Policy between Sovereignism and Pro-Europeanism

Katarzyna Kochlöffel and Daniel Šitera demonstrate how one year after the so-called pro-European Civic Coalition took power in Poland, the announced shift from the Law and Justice sovereignist foreign policy has proven more complex than expected.

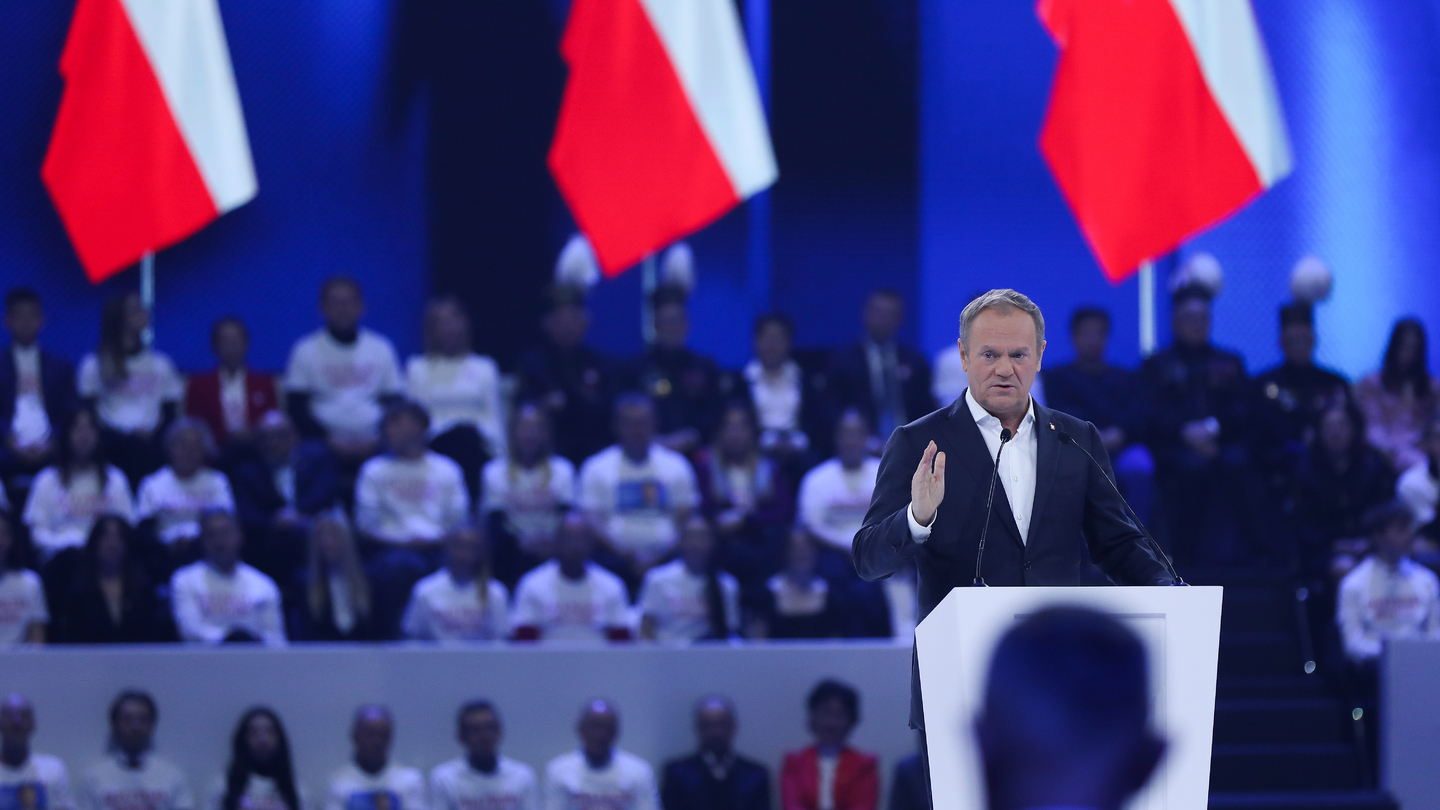

It has been one year since Donald Tusk’s Civic Coalition (KO)-led pro-European government took power in Poland, which ended the eight years of sovereignist foreign policy under Law and Justice (PiS). The return of Tusk as Prime Minister and Radosław Sikorski as Minister of Foreign Affairs was heralded as Poland’s shift from the margins to the EU policymaking mainstream. This return was framed as a complete overhaul whereby Warsaw would no longer lambast Brussels or Germany in the West, reverse the trend of worsening relations with Ukraine in the East, and distance itself from the sovereigntists in Central Europe. However, the promised pro-European change has been consciously combined with a PiS-like sovereignist continuity in the practice and rhetoric of KO-led foreign policy.

This chapter explores the mainstreaming of the sovereignist approach in foreign policy: a pro-European liberal-conservative mainstream imitating the radical conservative or far-right foreign-policy rhetoric and practice in search of popular support, and normalizing it in effect. Several factors influence this continuity in the Polish context. Some reflect the basics of the Polish national interest towards Russia and the EU-level politics, which are shared by the two parties. Others are more conjunctural such as the PiS-affiliated President Andrzej Duda’s authority in formulating the country’s foreign policy. The prevalence of continuity over change is a complex outcome of the PiS’s foreign policy, having been a driver and symptom of the Tusk government’s sovereignist domestic and the EU´s international positioning.

This chapter interprets how the KO’s sovereignist foreign policy deepened the continuity in the country’s approach to the issues of war and migration, and relations with Germany, Ukraine, and (Central) Europe. For Czechia, as Poland’s close partner, this requires a more pragmatic approach that balances the risks and opportunities resulting from this continuity.

Sovereignist Continuity

Shortly after winning the elections, Tusk announced Poland’s return to the pro-European mainstream in the EU. However, his exposé as the new Prime Minister has already implicitly mimicked PiS’s triumphalist rhetoric of we-told-you-so against unwilling Western partners in regard to the key foreign and security policy issues. During 2024, this rhetorical continuity has been deepened and turned explicitly into practice.

Warsaw has continued in critiquing Germany’s assumed appeasement policy toward Russia and self-limiting engagement in the military support for Ukraine. When commenting on the German investigation into the destruction of Nord Stream 2, Tusk stated that the “only thing you should do today is apologize and remain silent”. Even the problem of WWII reparations, which is often seen as an example of PiS’s anti-German politics, remained a key agenda topic during the annual governmental consultations.

The mix of support and conditionalities vis-à-vis Ukraine has also continued. This included the conflict initiated by PiS over the grain trade and the long-lasting tensions related to the politics of memory, especially Ukraine’s recognition of the Volhynia massacre. Warsaw’s continuing support for Ukraine’s military and political ambitions is thus still conditioned upon Kyiv’s good will in terms of the Polish national interest.

In Central Europe, Warsaw’s divorce from Budapest and the Visegrád Four’s split into the “V2+V2” constellation was also long in the making. In 2022, Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine has broken up the special relationship between PiS and Hungary’s Fidesz. Tusk has deepened this conflict to the scale of an articulated antipathy between the two leaders and their countries. This was combined with a parallel situation in the Czech-Slovak relations, thus resulting in the V4’s split and a downgraded cooperation.

Finally, migration runs as a red line through the new government’s foreign policy. The new migration strategy titled “Taking Back Control, Ensuring Security” is the best evidence of PiS’s sovereignism mainstreaming. Switching from a humanitarian perspective on the pushbacks of migrants to he militarization of the Polish-Belarusian border, the new government continues in seeing the situation as a purely Russia-orchestrated hybrid war. Brussels is also challenged for imposing a migration diktat that allegedly threatens the member states’ security. Tusk’s harsh critique of Germany’s introduced border controls within the Schengen area confirms that migration has now, more than ever, been put into the center of Polish foreign policy.

New Context, New Rhetoric

Within this continuity, there has also been a gradual change. Thanks to Sikorski and Tusk’s well established position in the EU’s mainstream, the combination of a pro-European approach with a sovereignist rhetoric could be normalized, being seen as responding to the changing geopolitical context and security-related sentiments in Europe. It is also consistent with Warsaw’s long-term ambition to match Germany and France’s special position in the EU policymaking.

Despite the Tusk government’s higher-than-expected level of rhetorical friction in relations with Germany, the qualitative (and quantitative) changes cannot be overlooked. They are evident in the increasing number of bilateral and minilateral meetings with German representatives alone or in the Weimar Triangle format, which points to the standardization of relations with Germany (and France). However, their impact on the Polish position within the EU has been ambiguous so far. On the one hand, Warsaw was able to win a strong budget portfolio for Piotr Serafin in the European Commission. On the other hand, Tusk was recently sidelined by Berlin during the Western leaders’ summit on Ukraine.

Contrary to general expectations, the new government deepened even further the transactional approach towards Ukraine. This was prominently done by the Minister of National Defense Władysław Kosiniak-Kamysz and his claim that “without commemorating the victims of Volhynia, Ukraine will not enter the EU”. This approach yielded short-term gains by pressuring Ukraine to take action on the matter; however, the methods used to enforce such a Polish-Ukrainian understanding may remain contentious in the long term. Additionally, the government rhetoric shifted from seeing the full support for Ukraine as a logical decision for Poland’s own safety in the manner of “who defends Ukraine defends oneself.” Rather, Sikorski recently stated that having done already more than others in this respect, Poland cannot weaken its military potential at the expense of helping Ukraine.

As the Polish V4 Presidency has de facto frozen the goup’s strategic activity, Warsaw has moved to deepening the V2 relations with Czechia while searching for alternatives in the Baltics and Northern Europe. The KO-led government has retained special Central European relations with Czechia in the context of the military support for Ukraine and other sectoral issues of energy security, nuclear energy, and infrastructure. Yet there have also been topics that made the rival duo of the pro-European Tusk and the sovereignist Viktor Orbán unexpected allies, especially their hard approach to the EU migrant relocation policy and the fight against so-called illegal migration. While this might be just another mainstreaming case of pro-Europeans trying to beat sovereignists on their own terms, it highlights how KO’s promised overhaul ironically represents a partial continuation of the PiS-like foreign policy approach.

Back to (the Future of) Central Europe

The pro-European shift within the sovereignist realms of Poland’s foreign policy has brought opportunities for the current political leadership in Prague. Indeed, the current political constellation of Petr Fiala’s government and President Petr Pavel is a mix of sovereignist and pro-European views on Central Europe, Germany, and Ukraine, especially when they concern war and migration in Europe. However, there are also risks involved.

On the Central European level, the closer Czech-Polish bilateral relations are a result of the deeper split in the Visegrád Four. Czechia might profit from this during Poland’s Presidency of the Council of the EU in 2025. On the other hand, this narrowed the cooperation space for Prague more than that for Warsaw, making Czechia more dependent on Poland or looser minilateral frameworks. The V4 leaders agree only on specific policies, such as the so-called illegal migration. Moreover, besides Slovenia and Austria, the alternatives of the Slavkov and Central Five frameworks include Hungary and Slovakia again.

Prague and Warsaw also share interests in preventing Berlin’s reintroduction of border controls due to migration and Germany’s decreasing support for Ukraine (Eberle in this volume). However, while working in tandem with a bigger player brings advantages, this also involves a risk of becoming part of the continuing rivalry between Berlin and Warsaw, which has not disappeared under the Tusk government.

Ukraine remains a top priority for both countries. However, in the areas of war and EU enlargement, while the Czech approach remains rather unconditional, Poland has moved further to a conditional one. Poland’s assertiveness gives Czechia an opportunity to move into a more pragmatic direction regarding the end of the war – as presented by President Pavel – and acknowledge the problems the enlargement can bring.14 Yet again, one must simultaneously pre-empt potential ruptures in Polish-Ukrainian relations that might contradict Czechia’s current priorities. In sum, when recognizing Poland as a key foreign partner, Prague should remain aware of the different tones in the shared interests and of the risks and opportunities involved.

→ The risks involve becoming too dependent on the Polish-Czech relations in Central (and Eastern) Europe. This bandwagoning can backfire as Czechia – despite all the shared interests – has a different and less burdened policy approach to Germany and Ukraine.

→ The opportunity stems from Poland’s attempt to strengthen the position of the pro-Ukrainian part of Central and Eastern Europe in the EU mainstream against the background of internal instability and the weakening influence of the big West European states in the EU policymaking.