Tunisia in 2022: Reforming the Institutions amidst Turmoil

paper

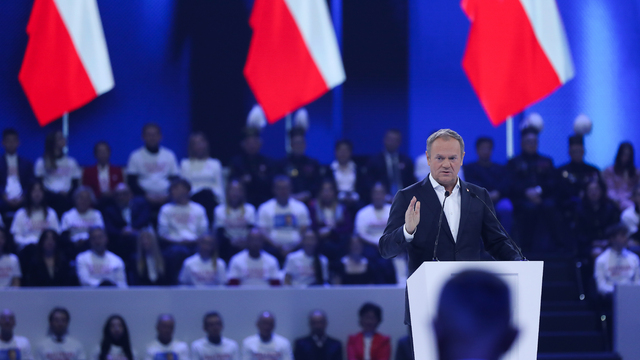

Tunisia entered political and institutional uncharted territories on July 25, 2021, when President Kais Saied proclaimed a state of emergency and suspended the parliament. Since then, the political scene has been divided into four groups that barely communicate with each other: the Islamist Ennahda, the Free Destourian Party, the “centrist” parties, and the supporters of Saied.

Kais Saied’s project to reform institutions has been met with scepticism from a large part of the political players. The official roadmap envisions a referendum on this question that is to be held by July before the election of a legislative assembly in December. The continued degradation of the economy and the deepening of social tensions could derail the whole process. In addition, the conflation of executive and legislative powers, and the arrests of several of Saied’s opponents worry large segments of both the

political class and the civil society. The army and the international community are broadly perceived as the only players potentially able to push forward a national dialogue.

In this context, the EU may help to build a new consensus in Tunisia. While supporting the efforts to solve the structural imbalances which feed the crisis, the EU needs to open channels of communication between the different political players and support the initiatives aiming at a more inclusive transition process. Lastly, the EU’s priority should be to insist on the preservation of human rights and freedoms by the authorities.

Introduction

In the frame of the European Neighbourhood Policy, the EU has been actively involved in the preservation of Tunisia’s stability and in the support for the Tunisian democratic transition. Thus, the derailing of the transitional process during the second half of 2021 constitutes a major concern for the EU. The failure of the only democratic experience to date in the region would compromise the stability of North Africa by preventing segments of the oppositions from participating in the elections and lead them to opt for more radical courses of action instead.

One of the main reasons behind the current crisis in Tunisia is the incapacity of the post-2011 political system to channel the interests of the segments of the population who participated in the revolution, mainly the youth and the inhabitants of the underdeveloped peripheral regions (in the West, the Centre, and the South). President Kais Saied has been elected in 2019 mainly due to the support of these demographics and his promise to achieve the goals of the revolution. The parliament elected the same year included political

parties able to attract the votes of the same groups: the Islamist Ennahda, the “Heart of Tunisia” of the tycoon Nabil Karoui (both now opposing Saied), and the Nasserist Echaab Movement. Other political forces (such as the social-democratic Ettayar or the centre-right Tahya Tounes and Afeq Tounes) were elected mainly by the populations of more developed urban coasts and the richer neighbourhoods of Tunis

The “July 25” Root Causes: Political Divisions and State Paralysis

The parliament that came out of 2019 elections was fragmented, with the biggest political party, Ennahda, controlling only 52 out of 217 seats. This led to governmental instability, which was worsened by economic issues and difficulties in coping with the Covid crisis. The Fakhfakh government (February–September 2020) was dominated by forces that approved Kais Saied’s policies (Echaab and Ettayar) with the support of Ennahda and Tahya Tounes (the main remnant of the formerly dominant Nidaa Tounes). After Elyes Fakhfakh being accused of a conflict of interest, Ennahda eventually caused his fall. This failure symbolizes the incapacity of the parliamentary system to address major underlying issues such as corruption and youth unemployment. The new government of Hichem Mechichi was supported by the so-called “New Troïka” (Ennahda, the Salafi “Dignity Coalition” and the neo-liberal “Heart of Tunisia”). However, not only were some members of this coalition accused of corruption, but also the tug of war between the presidency, the head of government and the parliament’s speaker (Rached Ghannouchi, the leader of Ennahda) led to a state of paralysis. A wide popular discontent started to manifest itself – especially in the Centre and the South – with the multiplication of protests against Ennahda, which was accused of being corrupt and infiltrating the state administration. In July 2021, the headquarters of the Islamist party have been burned down by protestors in several cities.

On July 25, President Saied reacted to this situation by declaring a state of exception and suspending the activities of the parliament, acting under a loose interpretation of article 80 of the 2014 Constitution. His justification for this move was that it would break the political deadlock between opposing political forces, and launch a fight against corruption. His decision was then backed by almost all the political forces, except for the “New Troïka”. Since then, Ennahda has been denouncing Saied’s move and calling for the reinstallation of the parliament. But the Islamist party has been isolated due to this attitude, as it was only supported by a handful of liberal personalities and small organizations, which were gathered within the “Citizens Against the Coup” movement. In addition, some prominent politicians (such as Abdellatif Mekki and Samir Dillou) and many cadres left the organization and are currently seeking to create a rival Islamist political party. At the same time, the popularity of Kais Saied has been also crumbling due to the long delay in appointing a government and several antagonizing decisions.

On September 22, Presidential Decree no. 117 concentrated legislative and executive powers in the hands of Saied, while abolishing the provisional body for monitoring the constitutionality of laws. The decree worried the “centrist” (liberal and social-democratic) parties in addition to the powerful trade-union federation UGTT. Since then, this part of the political spectrum has been asking for a clear roadmap, and for being

consulted on the decisions of the presidency. Another kind of opposition stems from the Free Destourian Party (PDL), which is nostalgic for the Ben Ali regime and has ranked first in the electoral polls until now (ca. 30%). This party has denounced the decree as well and has been calling for disbanding the parliament and holding the anticipated elections. Since September, the only political forces fully supporting Kais Saied are the Arab nationalists (Echaab, the Baath) and the loose organizations which participated in his campaign in 2019 and the demonstrations preceding July 25. Among them, the most important are the Free Tunisian Forces (FTL, led by Redha Mekki, alias “Lenin”) and the Movement of Tunisian Youth (MJT). The latter is close to the Arab nationalists’ views, but also draws inspiration from the French Yellow Vest Movement of 2018, and “Iceland’s Revolution” of 2009.

On November 19, the president’s refusal to promulgate a law on the integration of longterm unemployed graduates into the administration put him at risk of losing a part of his supporters. This decision antagonized some of the classic Arab nationalists (especially Echaab, which was at the initiative of this law), who think that the social situation is a priority and needs to be dealt with by the state. On the other hand, forces such as the MJT consider that the reform of the institutions will eventually “give the power back to the people” and that they will solve the pressing social and economic issues by themselves.

Currently, the political scene is roughly divided into four blocs with antithetical attitudes regarding the stance towards the political developments and proposals on the table: the Islamists, the Free Destourians, the supporters of the president, and the centrist parties.

A Contested Roadmap Aiming at Institutional Reforms

Some of the most worrying trends characterizing the current crisis started to develop during the preceding period, and particularly under the Mechichi government. The most pressing ones are the economic crisis and social unrest, the growing (multi)polarization of the political scene, the lack of communication between its constitutive elements, the decreasing influence of the parliament, and the growing number of arbitrary practices and procedures of the security apparatus, particularly following the adoption of the 2015 anti-terror law. The July 25 move resolved only the most pressing issue of that time: the state paralysis caused by the tug of war between “the three presidents” (of the Republic, the government, and the parliament). Kais Saied’s recourse to article 80 and the centralization of power in his hands raised hopes that he would tackle the structural issues inherited from Ben Ali’s regime: the territorial imbalance, youth unemployment, and endemic corruption. Nevertheless, it is doubtful that the president could do so without solving first the economic crisis and the political divisions. He and a part of his supporters believe the solution to all

these issues lies in the reform of the political system.

Since 2011, Saied’s goal has been to marginalize political parties by implementing a semidirect democracy (elections at several levels starting in the smaller districts, with drawing of lots and revocability of the representatives). This idea came from Redha Mekki (“Lenin”) and is supported by most of the movements backing the president (to the exclusion of the classic Arab nationalists: the Nasserists and Baathists), such as the MJT and smaller “organizations” (which are often mere Facebook pages). These players should not be

underestimated, especially with regard to the polls, which rank a virtual “Kais Saied’s party” at the same level of support as the counter-revolutionary PDL (ca. 30%). Saied’s project is popular among the youth and the inhabitants of the periphery, who elected him with the hope to end the “rule of political parties”. Consequently, these parties are very critical of the proposed reforms. Some expressed concerns are about the lack of feasibility of the project, the inability of such a system to select competent candidates and its potential abuse by local barons involved in the black market and smuggling. Supporters of the project, however, assure its critics that the revocability of the representatives would limit these risks.

On December 13, President Saied announced a roadmap that includes a referendum on the institutional reforms to be held on July 25, 2022, and legislative elections to be organized under the future new system on December 17, 2022. Meanwhile, the parliament will stay frozen, and the president will keep most of the state power in his hands. An online consultation has started on January 15, and will last until March 20, and its purpose is to gather suggestions for constitutional reforms. Then a committee of experts will draft a project for June, one month before the planned referendum. The roadmap pushed some centrist organizations to radicalize their opposition to Kais Saied, and to denounce the plan as a coup. On the other hand, Arab nationalists still support it despite not being convinced by the president’s ideas about the reform of the institutions.

In general, the proposed roadmap is worrying for most of the political players. This is so not only because it potentially puts them at risk of marginalization, but also because they feel that the schedule does not correspond to the urgency of the economic and social situation. Even before its announcement, many actors were expressing the idea that Saied’s July 25 move had merely permitted him to buy some time, but the threats of economic bankruptcy and state collapse were still unaddressed.

Economic Difficulties, Social Unrest, and the Spectre of Political Repression

The Tunisian economy, which was already experiencing difficulties prior to the Covid pandemic, has been heavily affected by it. The public debt is not sustainable anymore, leading to delays in the payment of civil servants’ wages. Foreign donors, starting with the IMF, condition their aid on a broad support of the main social partners (such as the workers’ union UGTT, the employers’ organization UTICA, and the agriculture union UTAP). However, there is no form of broad agreement on reforms there and most of the political

players deplore Kais Saied’s refusal to consult his decisions with them or even with the unions. This is not a problem only of the president as the four main blocks constitutive of the political scene barely communicate with each other. Certainly, the UGTT (and to a lesser extent the UTICA) maintain channels of communication with most of the political players on the one hand, and with the presidency and the government of Najla Bouden (appointed on September 29) on the other. Nevertheless, the meetings between the authorities and the unions remain sporadic, and on January 4, the UGTT openly criticized the presidential roadmap, fearing it would lead to personal power and the exclusion of the opposition.

Economic difficulties worsen social tensions, and feed protests, which usually confront the state. The last months of 2021 have been marked by a crisis regarding the collection of garbage in Sfax, the second most populous city of the country, on the south-eastern coast. Due to environmental concerns, its inhabitants had asked for, and obtained, the closing of the biggest dump of the governorate. Therefore, garbage accumulated in the streets of Sfax and the surrounding cities. After a campaign of civil disobedience, and under the pressure of a call for a general strike in the city launched by the UGTT, garbage collection has started again on December 8, concluding a two-month crisis. Another crisis erupted in November in the southernmost governorate of Tatouine. In the related protests, the protesters were asking for the local development plan that had been promised by the Mechichi government one year before, to finally be implemented. They threatened to close oil production valves – as they already did in 2017 – if their revendications were not met with tangible action from the state. These developments are particularly worrying for Kais Saied, who built a part of his electoral appeal on his promise to fight territorial underdevelopment. His main project related to this matter is asking corrupt businessmen to invest in local development projects in exchange for an amnesty.

Lastly, some recent arrests raised the spectre of political repression targeting the government’s opponents. On December 31, the deputy president of Ennahda and former Minister of Justice Noureddine Bhiri was violently arrested in front of his home before being transferred to a hospital two days later. Another cadre of the organization, Fathi Baldi, a former councillor of the Minister of Interior, was arrested the same day. Both are suspected of terrorism according to the authorities. However, Islamists are not the only targets of judicial procedures, and some media and activists question the independence of the judicial branch. Of course, this judicial timing should be put in relation to the lifting of parliamentary immunity on July 25. Nevertheless, Human Rights Watch has been denouncing the “arbitrary detentions” targeting the government’s opponents, and the Union of Tunisian Journalists estimates that freedom of speech in Tunisia is under an imminent threat.

Conclusion

The centrist parties – and with them the powerful UGTT, which gathers one million workers – are more and more critical towards Kais Saied. The president is still able to keep the initiative only because the opposition is divided into three rival groups of roughly equal strength: the centrists, the Free Destourians, and the Islamists. Nevertheless, the will to implement a system of “direct democracy” risks breaking the ranks of the

president’s supporters into the forces which supported him in 2019 and the classic Arab nationalists, who do not believe in such a system.

In addition, the opposition is tempted to answer the concentration of powers and the threats of repression with its own anti-democratic claims. Even among the centrists, the idea that the state is still at risk of collapsing is ever present, and some of them draw a parallel with Lebanon or even Libya in this regard. Many actors also think that the UGTT – which succeeded in imposing a political consensus that ended the 2013 crisis – is not able to initiate a national dialogue anymore due to its internal divisions, the proximity of its

congress in February, and its lack of coordination with the UTICA. Thus, the army and the international community are often mentioned as the only players that would be currently able to put all the sides around the negotiating table.

Indeed, to succeed, the institutional reforms should lead to an association of both the segments of the population which voted for Saied in 2019 (namely the youth and the inhabitants of underdeveloped regions) and his opponents. An inclusive process is the only way to save the democratic gains accumulated since 2011. The EU has a role to play in the establishment of such a solution.

Policy Recommendations

→ Funding: Financial assistance should address primarily the structural problems which derailed the democratic transition: the territorial imbalance, youth unemployment, and corruption. The EU should work with the member states toward a restructuration of the Tunisian debt and consider the cancellation of its

own part of this debt.

→ Capacity building: The EU should provide capacity building to civil society organizations working in the three above-mentioned fields. It should empower the UGTT in its initiatives toward the implementation of a national dialogue.

→ Communication: The EU should try to open channels of communication between the different political players (including the movements supporting Kais Saied). It should also insist on the preservation of human rights and freedoms, while refraining from public declarations, which are always susceptible to being

instrumentalized by one camp against another.

→ Expertise: The EU should offer assistance with the consultation process prior to the constitutional referendum, and also with the organization of free and fair elections in 2022.