The Corporate Scramble for Africa and its Unintended Consequences

Mezinárodní Politika has established cooperation with the Peace Research Center Prague, a newly-established interdisciplinary center of excellence at the Charles University, with focus on prevention, management, and transformation of conflicts in world politics. This article is part of the policy brief series published by the PRCP and Mezinárodní Politika. For more information, visit http://prcprague.cz.

Some time ago, in Japan, the Seventh Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD7) concluded in an optimistic spirit with the plan to boost Japanese private investment in Africa. However, this outcome of the conference has to be interpreted within the broader picture of international investment flows. We are currently living in an age in which the traditional instruments of economic development through the provision of loans and Official Development Assistance (ODA) are accompanied by an increasing rate and volume in bilateral foreign direct investment. This shift, however, has the potential to engender new and politically unintended consequences as we should expect more diplomatic, political and military foreign meddling in countries that face internal armed unrest and jeopardize existing foreign direct investment.

To understand the transformation from loans to investments, it is worth briefly looking back to the 1990s when TICAD began. From a historical perspective, the first TICAD was already convened as early as 1993 when Africa was marred by the repercussions of foreign aid withdrawal by Western countries and the Soviet Union in the wake of the end of the Cold War. While in the early days of TICAD development aid constituted the paramount instrument to support African societies in their pursuit of economic prosperity and the reduction of poverty, TICAD7 featured a high participation rate of Japanese small- and medium sized businesses ready to discover investment opportunities.

However, Japan is only one of many countries which incentivizes foreign direct investment to the African continent. Another active contributor to foreign direct investments into Africa is China. Similar to Japan, China has already organized three FOCAC Summits (the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation) since 2006 and pledged to provide $10 billion (out of a $60 billion package) through development banks like the China Development Bank to foster, explicitly, Chinese investment between 2018 and 2021. These economic investments intersect with the wider political ambitions of China and its Belt and Road Initiative.

Western states and organizations have entered into the competition for investment in Africa. The G20 Summit in Hamburg in 2017 created, under German leadership, the G20 Compact with Africa initiative (CwA). In a nutshell, the CwA provides an institutional framework in which interested African countries directly meet with G20 members as well as international financial organizations like the World Bank, IMF or the African Development Bank and are advised to change regulatory, institutional or economic frameworks to encourage foreign direct investment into their countries. Other notable ongoing initiatives are the EU-Africa Business Forum held in 2017 to foster EU corporate investment in Africa, the US-Africa Business Summit convened in June 2019 and the American Prosper Africa project, the Turkey-Africa Economic and Business Forum, and the India-Africa Forum Summit which took place in 2015.

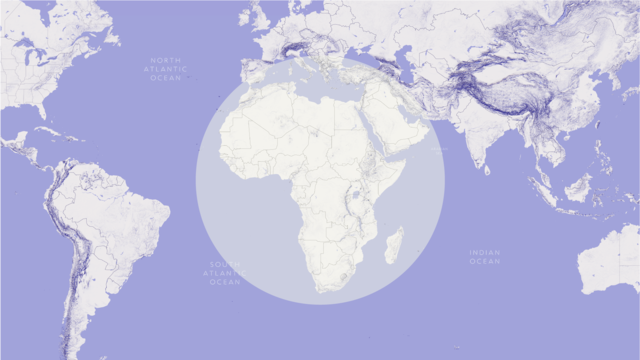

The consequences of this corporate scramble for Africa can already be observed in raw statistics. According to data from the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development from 2017, the three largest investors into the African continent are France with $64 billion FDI instock, the Netherlands with $63 billion and the United States with $50 billion follow by the United Kingdom ($46 billion), China ($43 billion), Italy ($28 billion), South Africa ($27 billion), Singapore ($19 billion), Hong Kong ($16 billion) and India ($13 billion). Whereas the rest of the world is experiencing a decline in investment, the African continent actually witnessed an increase of 11% from 2017 to 2018.

Africa is however not just the destination of the largest relative increase in FDI but also home to the world’s most politically unstable countries. The Upsala Conflict Database Project records ongoing armed conflicts between governments and rebel groups in 17 countries. Countries like Algeria, Mali, Burkina Faso and Libya whose territories incorporate the Sahara and Sahel face Islamist insurgents who defy the institutional authority of central governments. Other countries like Rwanda, Cameroon and South Sudan face home-grown rebel groups based on cultural, linguistic or ethnic lines. This is just a fraction of all of the existing conflicts as inter-communal violence is also high in Sub-Saharan Africa.

As foreign direct investment pours into Africa, it will inevitably become entangled with these domestic armed conflicts and thus jeopardize the value of the investments and put corporate personnel at risk. A textbook example is Nigeria where oil giants like Exxon Mobile, Chevron, Shell, Petrobras and Total maintain offshore oil rigs not far from the coast. Until 2013, MEND rebels from the Niger Delta used sophisticated hit-and-run tactics with speed boats to destroy pipelines, rob or kidnap personnel to extort ransom from the oil companies. Another example is constituted by Libya which throughout its entire civil war since the end of 2010 has witnessed intense fighting over oil terminals at its coastline at the famous “oil crescent”.

These two parallel developments, namely the increase in foreign direct investment and the presence of political and non-political armed unrest in Africa will influence the political decision-making process of countries with growing investment. Corporate executives will lobby for protection and interventions in their respective home countries against the backdrop of uncertainty over property rights. Politicians in the home countries, where corporations locate their headquarters, face the dilemma of balancing their public obligation to assist nationals abroad and their political interest to foster outward foreign direct investment with the costs inflicted on their constituents through interventionist measures and the risks that investors have to bear as part of market uncertainty.

History shows that there have been several instances in which the home countries used a wide range of instruments for the protection of their nationals’ investments in times of armed conflict. France sent special forces in 2013 to protect uranium production facilities of the French corporation Areva in Niger against Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb and its affiliates. Several years earlier in 2002, the United States government provided an extensive $8.5 billion aid package over several years called “Plan Colombia” which was primarily invested in Colombia’s military and police forces to counter the threat of FARC and ELN rebels. An additional $99 million was provided under a counter-terrorism scheme to protect, explicitly, the Caño Limón oil pipeline which was being operated by the American company Occidental Petroleum in the region of Arauca.

The pull factor of foreign direct investment can be so strong that the home countries even contradict their own stated foreign policy doctrines. Two fundamental foreign policy guidelines of China, which are based on the Five Principles of Peaceful Coexistence, consist of “mutual respect for sovereignty and territorial integrity” and “non-interference in each other’s internal affairs.” These two principles, however, did not stop China from calling out the Malian government in 2012 to protect Chinese investments and personnel in its country, an unprecedent move. A more striking example is the first Chinese participation in peace talks surrounding a civil war. In 2015, China became involved in the IGAD-PLUS framework to resolve the South Sudanese civil war, a country in which the oil giants China National Petroleum Company (CNPC) and Sinopec have provided foreign direct investment.

The consequences of the pull factor exerted by foreign direct investment on the home countries are manifold. First, the home countries with outward FDI to Africa will inevitably become more entangled with domestic-level political processes. Many countries who are top FDI recipients like Congo, Ethiopia and Egypt face volatile political conditions. Hence, investing countries will more attentively scrutinize political reforms in the recipient countries and voice their concerns when “their” FDI will be in jeopardy. Internal stability will become a paramount preoccupation for investing countries.

This points to the second related consequence, namely that in order to achieve internal stability in the recipient countries, investing states have a much higher incentive to support the status quo than in allowing the uncertainty of government turnover through a violent conflict. Investors are inclined to support the incumbent government as a guarantor of stability. This poses a dilemma for many corporations from Western states as well as their home governments since support for political movements can entail the loss of market access by the host government. In contrast, a country like China has been accused of providing Information and Communications Technology (ICT) which provides more capabilities to African states to quell dissident movements.

Third, the pull factor of FDI contradicts the political goal of the investing and recipient states to respect non-interference in domestic political processes. A fundamental critique of official development assistance has always been its inefficiency and its unintended consequence of propping up corrupt governments and ruling elites to the detriment of the local population in recipient countries. There has been a shift in thought away from the traditional instruments to foster FDI as a new panacea against developmental shortcomings. The Sustainable Development Goals proclaimed by the United Nations are explicitly tied to corporate investment. Hence, corporate investment might actually lead to more undesired future interference.

Fourth, potential foreign investors can be more inclined to support rebel factions in African countries if they are unsatisfied with an incumbent government. An extreme and infamous example is the alleged planned coup d'état in Equatorial Guinea. In 2004, a group of British investors organized mercenaries, with the majority coming from South Africa, to implement a coup d'état against the long-standing ruler Teodoro Obiang. Eventually this plan was foiled, and the mercenaries put in custody in Zimbabwe. In the process of FDI liberalization, rebel groups may in particular appeal to potential investors and offer in exchange for support of their struggle access to the country’s market. Researcher Michal Ross called this phenomenon “Booty Futures” in his analysis of natural resources.

The fundamental problem for African states as potential harbors of FDI is their weaker bargaining position vis-à-vis large investors. To boost their economies and gain legitimacy, African governments rely on foreign direct investment inflow as it provides jobs, transfer of technological skills, human capital and cash inflow. Due to their weaker macro-economic situation, movements of financial and human capital to and from their countries can entail disproportionally large effects on their economies, internal stability and social cohesion. Hence, African governments are dependent on ensuring as much FDI as possible to increase their public appeal and to stay in power which adds to the increased rates of FDI inflows.

Two solutions can be proposed to mitigate some of the detrimental effects of FDI on future political interference by the home countries in host states. One obvious possible solution to counter over-dependence is for African states to put an emphasis on diversification. Diversification allows incumbent governments to be less dependent on investment inflow from a particular country and increases their political leverage to counter unwarranted intervention. The current momentum in the international economy poses a unique opportunity for African states to invite a wide array of potential investors to their countries. Today a broad spectrum of investors from Europe, Australia, North America, East and South Asia, the Middle East and even South America is poised to invest in Africa.

This leads to the second possibility, namely to establish clear guidelines in Bilateral Investment Treaties (BITs) in the case of armed unrest which puts existing foreign direct investments in jeopardy. So far, every recently concluded BIT includes a clause stating that “restitution, indemnification, compensation or other settlement” for damage or loss in investments has to be accorded to the signed party in the same manner as granted to investors who do not participate in the BIT. Some BITs further state that actions or deliberate negligence by the armed forces of one of the signed parties, which lead to damage or loss of foreign direct investment, constitute a reason for compensation. The drawback of this procedure are lengthy disputes in arbitration courts and the uncertainty for investors regarding whether they will see their invested money back at all.

A potential instrument that mitigates the needs of an investing state to intervene could be created through a compensation fund which should be established by the signatories of the BIT. Such a compensation fund would consist of a limited but dynamically changing amount of available capital (depending on the volume of FDI) to offset losses of investors in times of armed conflict. Part of the compensation fund would be contributed by the signatory states and a further part would be contributed by investors that want to insure their investments against potential losses. Such a configuration would have several advantages. First, signatory states would be only liable to a fixed threshold. Second, corporate and political actors would lose legitimacy in calling for interventions as a compensation scheme would be in place. Third, corporations would have more certainty that their damage and losses would be compensated and would be more inclined to invest. Fourth, the compensation process would be legally facilitated, faster and less costly than the current mode which requires the involvement of international arbitration courts.

Those are two recommendations, but they are by far not exhaustive. However, if no action is taken to prevent the unintended consequences of foreign direct investment in Africa, then both investors and recipients will experience political dilemmas. On the one hand, investing countries, who resort to FDI instead of ODA as an instrument for development, will inadvertently face the tough choice of whether to intervene when foreign direct investment is at risk. On the other hand, African states, which hope that FDI will be politically less intrusive than ODA, may find themselves in the opposite situation, namely one in which investors will be more inclined to influence domestic-level processes. Moreover, it seems that the trend of FDI flows to Africa is not coming to a halt anytime soon. The next large convention on African development is already just around the corner. In October 2019, the first Russia-Africa Conference in history will take place.