Militarisation of space and nuclear weapons

In February 2024, the U.S. accused Russia of developing an anti-satellite (ASAT) weapon with a nuclear payload for low-Earth orbit, drawing attention amid escalating U.S.-Russian tensions and nuclear conflict risks. This reflection reviews the allegations, key international laws preventing space-based weapons of mass destruction, and efforts to avoid an arms race in space. It highlights recommendations from former NATO Deputy Secretary Rose Gottemoeller on reducing conventional and nuclear risks in Europe and refers to expert opinions from SIPRI. The reflection warns of the dangers of space militarisation and calls for renewed arms control talks between rival nations.

In the first half of February 2024, the U.S. accusing Russia of develoing anti-satellite (ASAT) weapon with a nuclear payload and intending to place it in low-Earth orbit attracted attention. This came at a time of increasingly tense US-Russian security relations and the growing threat of a nuclear conflict. This reflection recounts the circumstances surrounding the publication of the allegations and describes the main international legal instruments preventing the deployment of weapons of mass destruction in space. It also provides a brief history of efforts to prevent an arms race in space. In response to the continuation of the Russia-Ukraine conflict, and the risk of an increase in deterrence between NATO and Russia, the reflection highlights some of the recommendations of former US Deputy Secretary General of NATO and leading arms control expert Rose Gottemoeller, which she made with the aim to reduce the risk of conventional and nuclear confrontation in Europe. It also recalls similarly focused articles by several arms control experts of the prestigious non-governmental institution Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI).

It concludes by pointing out the possible negative consequences of the potential militarisation of space and the launch of arms races in this area. At the same time, it expresses support for the resumption of arms control negotiations between the main rival countries.

THE URGENCY OF THE PROBLEM

The militarisation of space refers to the deployment of offensive assets such as anti-satellites and laser weapons in space. So far, no power with a space programme has officially confirmed the practical implementation of such a move on its part. On the other hand, the military use of space for non-offensive and passive military purposes has long been ongoing and is indispensable for air defence, among other thisngs. Military satellites are serving, for example, as early warning, communications satellites and sensors. In some cases, commercial satellites are also used. In a February issue of the UK’s weekly Editor’s Digest of The Financial Times, an article by Michael Peel, Clive Cookson and Jon Paul Rauthbenes gives the projected numbers of military satellites of the major nuclear powers. The US is said to have 247, the PRC 157 and the RF 110. To give three other examples, France, Israel and the UK were said to have 15, 12 and 6 of these satellites in their possession at the time respectively.

At the time of the Cold War, the so called Star Wasr programme, as the Strategic Defence Initiative (SDI) of the 1983 Republican administration of Ronald Reagan was sometimes called, already envisaged, among other things, the deployment of Space Based Interceptors (SBI). However, the SDI programme was prematurely terminated due to technological problems and enourmous financial costs.

After the end of the Cold War, four countries (the RF, the USA, the PRC and India) already demonstrated their capability to destroy satellite assets with a ground-based anti-satellite missile by shooting down their own malfunctioning satellites. However, from the point of view of the safe peaceful use of outer space, these tests pose a danger of an excessive increase in space debris. Currently, there are around 9,500 active satellites orbiting the Earth in various orbits, including two manned stations (the International Space Station and the Chinese Tiagong space station).

The above mentioned US accusation appeared in the first half of February of this year in a statement by the Republican chairman of the US Congress House Intelligence Committee, Michael Turner. It was based on unspecified US intelligence findings and its publication was justified by a fearing of a serious threat to the country’s security. As a result, President Biden and other US officials briefed both houses of Congress as well as allied and partner countries on the issue. The Russian side denied the accusations in a Feb. 15 statement by Kremlin spokesman Dmitry Peskov. Days later, President Vladimir Putin also commented on the allegations, according to the Russian magazine Kommersant. He categorically denied the accusations, saying that Russia had always called for compliance with all international legal instruments related to this issue. The Russian side cited as likely motives for the timing of the accusation the efforts of supporters of military aid to Ukraine to gain support in Congress for its approval and U.S. efforts to push for the resumption of the U.S.-Russian strategic dialogue. Russia officially rejected this dialogue in December 2023. One of the main reasons for the rejection is the massive U.S. military aid to Ukraine, which was described by Russian officials as a threat to Russia’s “vital interests” and an effort to “strategically defeat” it. Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, in an appearance on the Arabic TV channel Al-Jazeera earlier this year, even characterized the current situation as the US “hybrid war” against Russia.

US Secretary of State Antony J. Blinken discussed the charges with his counterparts from the PRC and India in the second half of February at a security conference in Munich. He warned them of, among other things, the consequences of pursuing such an option for space-based peacekeeping programmes and asked them to influence the Russian leadership to back away from the said plan.

In April, the US submitted a US-Japanese draft resolution to the UN Security Council (UNSC) calling for a ban on the deployment of nuclear-weapon satellites in the Earth’s orbit. Russia vetoed the proposal, arguing that the requested ban applied only to weapons of mass destruction and not to other offensive weapons. Two subsequent Russian draft resolutions, supported by China, among others, failed to gain support in the UNSC in April and May. The fundamental inconsistency in the positions of the two sides on the wording of the resolution thus illustrates their long-standing divergent approaches to dealing with the prevention of an arms race in outer space. The debate on the resolution has been taking place from the Cold War to the present in the plenary at the UN General Assembly (UNGA) and its 1st Committee (on Disarmament and International Security), and in particular at the Conference on Disarmament (CD) in Geneva under the English acronym PAROS.

THE MAIN INTERNATIONAL LEGAL INSTRUMENTS RELATING TO OUTER SPACE

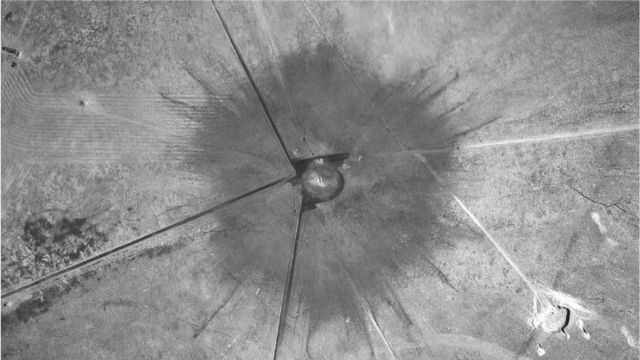

During the Cold War, the US and the then Soviet Union conducted several nuclear tests in outer space. The US conducted these tests over the Pacific Ocean in 1958–1962, and the Soviet Union over Kazakhstan in 1961 and 1962. They resulted in the crippling of several satellites and telecommunications links, mainly due to the electromagnetic pulse and radiation that are among the concomitants of a nuclear explosion. The destructive effects of the tests thus demonstrated the potential use of a nuclear explosion as an anti- satellite weapon (ASAT). According to the American Physical Society report of 2022, this destructiveness was demonstrated, for example, by the US’s most powerful nuclear test, Starfish Prime, with a warhead explosive yield of 1.4 MT of a conventional trinitrotoluene equivalent (TNT). The test occurred at an altitude of 400 km above Johnson Atoll.

As a result of the negative effects of these tests, the two countries negotiated the Treaty on the Prohibition of Nuclear Weapons Testing in the Atmosphere, Outer Space and Under Water (the Partial Test Ban Treaty, PTBT) in 1963. In terms of air defence construction, its significance lies in the prohibition of the use of nuclear warheads with anti-missile launchers. However, it does not prohibit other possible forms of deployment of offensive means in space, such as laser weapons or anti-missiles with a kinetic destructive capacity. The treaty also allows for underground nuclear testing.

However, the legal regulation of outer space and celestial bodies is based on the norms of the 1967 Treaty on Principles Governing the Activities of States in the Exploration and Use of Outer Space, including the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (the “Outer Space Treaty”, OST). While it prohibits the deployment of weapons of mass destruction in outer space, it does not prohibit, for example, the passage of ballistic missiles with nuclear warheads through the Earth’s orbit or the possible deployment of weapons systems that do not contain weapons of mass destruction. On the other hand, the OST already prohibits the deployment of any weapons, i.e., not only weapons of mass destruction, on the Moon and other celestial bodies. Therefore, in general, the OST Treaty provides for a regime of a partial non-militarisation of outer space and a full non-militarisation of the Moon and other celestial bodies.

The extension of the regime of the complete non-militarisation of the Moon and other celestial bodies was achieved by the adoption of the 1979 Agreement on the Activities of States on the Moon and Other Celestial Bodies (the Moon Agreement, MA). It prohibits the use of the Moon for any use of force or threat of force and for any other hostile acts or threats of such acts against the Earth, the Moon, space objects and spacecraft, including their crews.

THE HISTORY OF THE PREVENTION OF AN ARMS RACE IN OUTER SPACE

As stated in an article titled “The Conference on Disarmament and the Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space ”, published by the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR) in April 2011, the above-mentioned effort was launched during the Cold War. The author is Paul Meyer, a former Ambassador and a former Permanent Representative of Canada to the United Nations in Geneva. In the article, which describes developments from the 1980s to 2010, the author draws primarily on relevant UN Yearbooks, CD documents and his own experience.

In his introduction, Meyer points to the long-standing discussion of space issues from an arms control and disarmament perspective at the UNGA and the CD. It was prompted by the international community’s concern about the possibility of an arms race in space, due to rapid developments in space science and technology. The first national initiative to discuss this issue as a separate item at the UNGA was taken by the then Soviet Union in August 1981. Subsequently, the UNGA delegated the issue to the CD by an appropriate resolution requesting the negotiation of an agreement.

In the article, Meyer recalls, among other things, that in the debates on the subject, both at the UNGA and subsequently within the CD, there were, from the outset, divergent views among member states on the nature of the threat and on the generally acceptable way of dealing with it.

The item was placed on the CD agenda under the abbreviated title PAROS (Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space) in 1982. It was not until March 1985 that the CD reached consensus on the formation of an Ad Hoc Committee and its mandate to discuss PAROS. The nearly ten years of that committee, operating without achieving relevant results, is indicative of the continuing divergent approaches of the participating states to the problem. According to Meyer, the key issue during this period was the question of when to start the process of moving from a discussion to a negotiating mandate.

Even the end of the Cold War did not bring a fundamental reversal of this unfavourable development. Referring to the Report of the Chairman of the Ad Hoc Committee on Prevention of an Arms Race in Outer Space, document CD/642, of 24 August 1994, Meyer states, inter alia, that the Russian delegation pointed out the shortcomings of the then existing legislation, as it did not prevent the launching into space of conventional weapons or their testing. Some Western countries, on the other hand, argued that there was no arms race in space and therefore no need to create new or revise existing international legal instruments in this regard. At the same time, they stressed the need to strictly respect existing legislation and initiated and supported proposals to create international agencies to monitor space activities. Persistent disagreements, including those on transparency issues and confidence- building measures, led to the termination of the Committee in 1994.

Canada and the PRC attempted to reactivate the CD on the subject with compromise proposals in 1998–1999 and February 2000, respectively. The latter requested the reactivation of the Ad Hoc Committee on PAROS and attached a draft of the basic elements of an international legal instrument. In 2002, China and Russia presented a similar proposal jointly and in February 2008 both countries had already submitted a draft treaty on the Prevention of the Placement of Weapons in Outer Space (PPWT). In the same year, the European Union worked on a draft Code of Conduct for Outer Space Activities and submitted a revised version to the CD in 2010.

n the following years, the Russian-Chinese draft PPWT treaty was revised several times on the basis of critical comments, but to date it has not received sufficient support. The main critics of this initiative have long been the representatives of the US. At the CD meeting on March 30, 2023, US Ambassador Bruce Turner summarized the main US preferences in this area. These include a priority effort to reduce the risk of conflict in space. According to Turner, this should be accomplished primarily by complying with the norms of the international legal order, and assessing current and future threats to space activities, and the overall international security environment. As part of a gradual process, the relevant actions should develop principles and norms related to, for example, transparency, confidence-building measures and responsible behaviour. The U.S. also emphasizes respect for humanitarian law in space activities. This is related to the Russia-Ukraine conflict and Russian threats of an arguably legitimate retaliation against satellites providing support to the Ukrainian side. The main US criticisms also include a belief in the impossibility of verifying and enforcing compliance with any treaty.

The EU’s proposal for a Code of Conduct did not receive any significant support during the CD negotiations, even though it was a non-legally binding document.

ROSE GOTTEMOELLER’S RECOMMENDATIONS FOR REDUCING THE RISK OF NUCLEAR CONFRONTATION

In the context of this year’s 75th anniversary of NATO’s founding and the Alliance’s July summit in Washington, in a May interview, Rose Gottemoeller presented her ideas for a reflection on possible ways out of a nuclear weapons security crisis. She is an American former NATO Deputy Secretary General and the chief negotiator of the US-Russian Treaty on the Reduction of the Number of Deployed Strategic Nuclear Weapons (New START), signed in Prague by the presidents of both countries in 2010.

An interview with Rose Gottemoeller from May 1 was published by the American Bulletin of Atomic Scientists in an abridged version on July 29, 2024 under the title “Interview: Rose Gottemoeller on the precarious future of arms control”. In the part of the interview dealing with the termination of certain arms control treaties concluded by the US with the Soviet Union, the interviewee expressed, among other things, her personal opposition to these steps. These included the termination of the 1972 US-Soviet treaty on the limitation of missile defense systems (the ABM Treaty) and the cancellation of the 1987 treaty on intermediate and shorter-range ground-based missiles (the INF Treaty) by the Republican administrations of G. W. Bush Jr. and Donald Trump in 2001 and 2019, resprctively. She also stressed the need to continue negotiations with Russia on the reduction of strategic nuclear weapons with a so-called first strike capability and also on other issues. She justified the urgency of resuming negotiations with it on the basis of the existential threat posed by these weapons. (Note: the so-called strategic nuclear triad consists of nuclear warhead delivery systems with a range of over 5,500 km, which include land-based intercontinental ballistic missiles, strategic bomber aircrafts and nuclear submarines.)

She also considered nuclear sub-strategic second-strike weapons to be a worrying issue, which should also be discussed. These are medium- and shorter-range missiles with a flightrange between 500 and 5,500 km. The appointee also stated that the most important area in the arms control efforts of NATO countries was achieving a moratorium on the deployment of these weapons in Europe.

The Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) also published two commentaries on this issue by its arms control experts in the last two years. The first article, dated 5 December 2023, is entitled “More investment in nuclear deterrence will not make Europe safer”, while the second commentary, co-authored by SIPRI Director Dan Smith, is dated 26 March 2024 and is entitled “NATO: A new need for some old ideas”.

CONCLUSIONS AND FURTHER ANTICIPATED DEVELOPMENTS

An arms race in space could dangerously escalate the already tense relations between the major rival space powers. Its negative impact in terms of the deepening of the security crisis in the world and, last but not least, increasing the threat to the prosperity brought to humanity by the peaceful use of space cannot be ruled out.

There is the threat of a dangerous escalation of tensions and the dynamics of a spiral of arms races and mutual deterrence, with the concomitant phenomenon of action-reaction in US and NATO relations with Russia. The resumption of arms control negotiations pertaining to strategic stability and the adoption of measures to reduce the risk of conventional and nuclear conflict could undoubtedly contribute to mitigating this. However, the main prerequisite is an end to the Russian-Ukrainian conflict and the political will to address the long-term security challenges in Europe. Such a development could also have a positive impact on the resolutions of other crisis areas.