The Future of EU Enlargement in a Geopolitical Perspective

paper

Non-enlargement and delayed enlargement are active choices by the EU with concrete consequences. Maintaining the status quo is not an option. Enlargement processes are triggered by the application of a potential member state, and EU responses in the field encourage or discourage certain developments independently if we speak of the Western Balkans, Moldova, Georgia, or Ukraine.

Progress with the enlargement agenda anchors countries into European structures and serves as a confirmation of their European choice. However, as examples from the Western Balkans show, there is a concrete risk that the EU might end up legitimising autocratic regimes in a bid for progress. The enlargement process must therefore not be decoupled from a clear meritocratic scrutiny.

EU membership does not take place in a vacuum. As with previous enlargement rounds, the real security provider is NATO. The EU’s mutual defence clause is not a sufficient security guarantee. It is therefore difficult to conceive of a Ukrainian EU accession without NATO membership. After Ukraine’s accession, in particular the Ukraine army could be a substantial contribution to a European defence system.

Other external developments might also contribute to the EU’s development of strategic autonomy.

The nine accession countries would contribute with access to raw materials, including critical and strategic raw materials. For instance, Ukraine has a shared third in the world processing of the critical resource material scandium and has the second largest deposits of natural gas in Europe after Norway.

The growing size of the EU’s market would enhance the so-called Brussels effect and increase the global relevance of the EU. The nine accession countries would increase the EU’s population from 447 to 513 million. The less developed economies of the countries, however, would be a challenge for the EU’s economic, social, and territorial cohesion.

The time schedule for enlargement is crucial. Albeit it is never possible to guarantee a deadline year for enlargement, taking into account the conditionality-based process, setting a target year would be recommended to avoid overly optimistic assumptions in some candidate countries (e.g. Ukraine) as well as to clearly illuminate if EU member states are delaying the process.

INTRODUCTION: THE GEOPOLITICAL SITUATION AND THE CHANGED GEOGRAPHY OF THE EU

The European Commission has described enlargement as a ‘geostrategic investment in a strong, stable and united Europe based on common values’. The countries of the Western Balkans received membership prospects already in 2003, but when it comes to Ukraine, Moldova and Georgia, the possibility of their EU accession was confirmed only after Russia launched its attempted full-scale invasion of Ukraine in February 2002.

The granting of candidate status to Moldova and Ukraine in June 2022 meant a rupture with the previous geopolitical thinking within the EU on further enlargement. The 2009 Eastern Partnership is a clear example of the previous approach based on tying the Eastern Neighbourhood countries closer to the EU by utilising extensive free trade agreements but without promising membership. The EU’s changed geopolitical vision is an obvious result of the new geopolitical landscape. The option of grey-zones, or countries serving as bridges between a Russian sphere of influence and a Western one, is not attainable anymore and therefore it is difficult to find alternative visions of the EU that would challenge enlargement now, and it seems that the only thing that could alter this would be a radically changed Russia.

The war has brought enlargement high up on the EU’s agenda. Yet, since the enlargement process includes several veto points for member states and is time-consuming, there will be continuous negotiations between EU members with different preferences on the speed and feasibility of enlargement. It is nearly impossible to state a firm deadline for complex meritocratic processes such as enlargement. On the other hand, if this were not done, that would increase the risk of a standstill. The year 2030 as a target year for the completion of a big enlargement wave, including Ukraine, has been suggested by Charles Michel, among others, and appears reasonable since it would both lower and increase expectations. A target year would be useful while clarifying attempts to delay the process. The time schedule might be a bone of contention between candidate countries and the EU; for instance, Ukrainian Prime Minister Denys Shmyhal suggested a tight two-year timetable for securing EU membership.

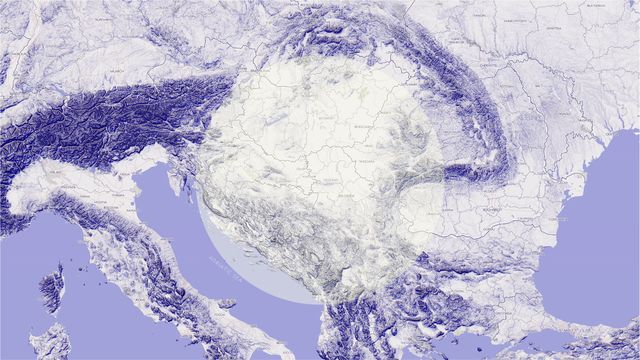

The changes to the EU that enlargement brings should not be underestimated. Enlargement would increase the EU’s population to about 506 million inhabitants and increase the labour force by 28 million people. The EU would be larger but, in economic terms, poorer. The EU centre of gravity would move in the direction of the Black Sea, with EU member states to the West, North and East of this area. The inclusion of the Western Balkans would further increase the amount of small-sized states in the EU, which could complicate decision-making. A speedy inclusion, however, could reduce Russian and Chinese influence in the area.

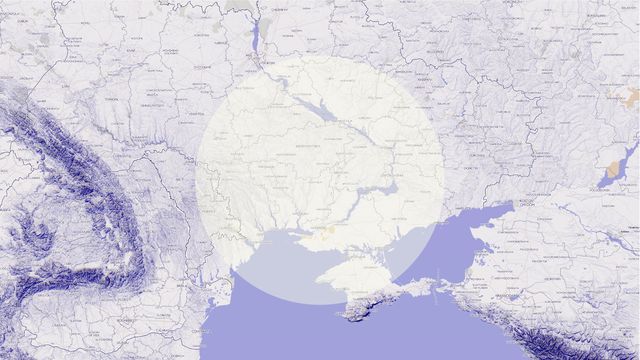

The most difficult aspect of enlargement is obviously Russia. If the EU enlarges to Ukraine, Georgia and Moldova, the EU’s border with Russia will expand in size and include contested areas. Moreover, even if the war in Ukraine comes to an end, that does not mean that the security dilemma will disappear. In addition, the enlargement to a geographically remote country such as Georgia, which lacks direct borders with other single-market countries, would also generate practical problems.

The paper is structured in the following way. We start with an examination of the security situation and the relationship between EU and NATO membership. Thereafter we continue with an analysis of the economic consequences of an enlargement to nine new member countries. The final part of the policy paper is then devoted to a detailed scrutiny of the enlargement to Ukraine and the Western Balkans.

NATO SECURITY

The long-term effects of any possible enlargement of the EU on security in Europe and around the world would depend on multiple factors-many of them being beyond the control of the EU–similarly as was the case throughout the existence of the Common Foreign and Security Policy. That applies with respect to effects on the EU-NATO relations especially. The EU has a credibility problem in security matters. The entry of Finland and the application of Sweden to join NATO vividly illustrated the level of trust in Helsinki and Stockholm with respect to the mutual defence clause of the Article 42(7) of the Treaty on European Union. Although the wording of the Art. 42(7) is seemingly stronger than that of Art. 5 of the Washington Treaty, in reality, countries clearly prefer NATO security guarantees. It won’t be any different in the case of Ukraine and therefore the character of the final outcome will largely depend on the position of the U.S. administration.

The enlarged EU will be motivated to significantly strengthen its internal cooperation and strategic autonomy in foreign-, security- and defence-related matters either way. A concomitant entry of Ukraine into NATO and the EU will provide Kyiv with necessary security guarantees vis-a-vis Russia, which will then enable Washington to dedicate more resources to the Indo-Pacific region and devote comparatively less attention to Europe than is the case right now. This reallocation of resources and persistent European concerns regarding a possible repetition of a Trump-like administration in Washington will motivate key European states to push for institutional reform of the CFSP and enhanced strategic autonomy in order to hedge against an uncertain future.

The very same dynamic, though maybe in an even stronger form, will emerge within the EU in the unlikely case of a potential EU enlargement without a prospect for a simultaneous entry of Ukraine into NATO. The EU will then be forced to boost the credibility of its own deterrence mechanism, which would require significant reform and improvements of the CSDP processes, including upgrades to the command and control system, military planning, ISR capability, and decision-making efficiency, eventually securing a complete strategic autonomy. Without these far-reaching reforms and in absence of a simultaneous NATO enlargement, it would be only a matter of time until a renewed aggression on the part of Russia would utterly shatter the credibility of the EU’s commitment to ensure the security of its member states, thus challenging the very idea of European integration. Given these considerations and some persistent problems in the EU-NATO cooperation, e.g. the Cyprus issue, it is highly unlikely that there will be a consensus on admitting Ukraine into the EU without a prior agreement on institutional and decision-making reform of the CFSD pushed by some West European countries.

Nevertheless, no such reform – including a strengthened strategic autonomy and a possible introduction of qualified majority voting into new issue areas – would, in the foreseeable future, be able to alter the fundamental division of labour between the EU and NATO according to which it is the Alliance that is the primary multilateral framework responsible for European defence. In terms dating back to the late 1990s, and bearing in mind the expected long-term antagonism with Russia, there won’t be any decoupling between

Europe and the United States in security matters and that is so in spite of the fact that there might be an increase in duplicity and discrimination between the two. NATO will continue to play an indispensable role in European security and the United States will be a partner of preference in defence-related matters, especially for Central and Eastern European countries. What is probably going to be the reality to an ever greater extent though is a degree of duplicity in existing efforts and discrimination in defence industrial cooperation. That is nothing new and it does not necessarily depend on a possible future CFSP institutional reform. For example, the introduction of qualified majority voting as part of a broader reform package triggered by enlargement can facilitate increased duplicity and discrimination by streamlining decision-making that would have required consensual compromises otherwise. But this trend has been set in the past already and it will not endanger the role of NATO.

Previous milestones in security and defence cooperation within the EU often resulted from external events, which ultimately led to lessons learned sanctioned by the Council decisions under the unanimity procedure and these were not necessarily spearheaded by biggerpicture treaty-based institutional reforms. The wars in former Yugoslavia, including the Kosovo conflict, were thus precursors to the Saint-Malo summit, the Helsinki Headline Goal and the EU Battlegroups. Similarly the Brexit referendum and the Trump administration in Washington served as enablers of the MPCC, the CARD, the European Defence Fund, and the PESCO revival. The war in Ukraine also pushed the Council to approve financing of weapons deliveries to Ukraine through the European Peace Facility, an unprecedented move given the previous practice. Especially the trend set by the creation of the MPCC and the EU-level capability development, including the CARD, bears unequivocal signs of duplicating existing efforts within NATO. Albeit marred by many deficiencies and conflicting interests, these duplications are here to stay and will be probably further reinforced in the future thanks to reforms motivated by the EU enlargement, among other reasons.

If perceived as part of a hedging strategy of the EU against future uncertainties, duplicity does not necessarily endanger transatlantic bonds, nor is it leading to a decoupling. The same applies for discrimination against U.S. companies in defence industry cooperation like PESCO. The defence industry is one of the most regulated and closely guarded segments of the economy. The related U.S. legal norms, including the International Traffic in Arms Regulations, the Buy America Act, and the United States Munitions List, are effective barriers preventing easy access of foreign defence companies (including European ones) to the U.S. market, and bending the international competition in favour of the U.S. industry. There is nothing extraordinary in similar efforts on the other side of the Atlantic. Mutual discrimination is an existing long-term practice, but only countries with major defence companies and globally competitive industries usually recognize this fact. Therefore, the urge to open up certain EU defence initiatives to non-EU countries should not be taken at face value, and the invitation of the United States or Canada to take part in the PESCO project on military mobility will not change the overall dynamic.

Probably the most significant effect of the EU enlargement on NATO will be associated with concomitant internal reforms of the EU functioning. But even these reforms will not change the overall pattern of the EU-NATO relations beyond strengthening some of the already existing trends. The EU enlargement will not lead to a decoupling between Europe and the United States even if the existing duplicity and discrimination might intensify over time thanks to a push for an enhanced strategic autonomy of the EU. That might possibly result from a streamlined decision-making but, most importantly, from external events beyond the control of the European Union.

ECONOMIC DIMENSION

If the EU does not enlarge, it will deprive itself of becoming a bigger consumer and investment market, and thus of its ability to increase its political clout in global economic and regulatory affairs. The accession countries would increase the EU’s labour force, investment opportunities, and raw materials resource base, as well as the bloc’s voice and representation in global governance. The size of the EU’s single market is behind the idea of its regulatory global superpower, which it attains through the so-called Brussels effect.

The bigger volume of and control over global resources and economic activity bring the EU a necessary economic weight and sovereignty which underpin this Brussels effect.

The enlargement from 27 to 36 states and from 447 million to 513 million consumers would significantly increase the EU’s Brussels effect. The new size would allow for creating effective regulations in the digital or green agendas, among other areas, without harming the EU’s own competitiveness. There are two sides of this effect. First, the multinational corporations adapt to the European regulation not only directly in the EU but, as a result, also indirectly in the rest of the world. Second, the EU can also promote the synchronization between the EU standards and bilateral or global standards when negotiating foreign trade agreements and through its influence in the international economic institutions. A notable example is the digital agenda, where the Brussels effect has been proven, e.g., in the case of data regulation, and is hoped to legitimize the standards set in the new acts, e.g., the AI Act.

The EU would also improve its international competitiveness and resilience, e.g., through enhancing its workforce and raw materials base. The candidate states would increase the EU labour force by almost 30 million people (no data for Kosovo) with advanced education. Their proportions of such people are close to the EU average of 76%, ranging from 67% in Ukraine to 81% in North Macedonia. Given that the candidate countries’ labour markets are already tightly connected with the EU through labour migration, the enlargement would reduce the transaction costs through the freedom of movement.

The engagement will also enable the EU’s resilience and competitiveness in global geopolitics and geoeconomics. In terms of global supply shares of raw materials, the nine accession countries have supply shares of at least slightly less than 0.1% in 33 raw materials. They supply nine of the critical raw materials (CRM) and two that fall under the category of strategic raw materials. Moreover, their supply involves both extraction and the advanced processing stages. These countries (alone or together) either have a higher capacity in this respect than the rest of the EU, or are only European leaders in both stages.

For example, Ukraine’s 4.2% share in the processing of the CRM scandium means that it belongs among the top six countries in the world in terms of this variable, with only Russia (16.7%) and China (66.7%) having higher shares. Ukraine, Georgia, and Serbia’s processing global share of the CRM manganese (approx. 5.8%) is almost twice the whole EU share (approx. 3,2%). In short, the costs of non-enlargement are high because the EU might miss the opportunity to increase its own economic size and resilience, or its regulatory influence in global economic affairs.

At the same time, the enlargement would also include costs and challenges. With the average rise in population being 14.5%, compared to the average GNI increase being 2.5%, the EU would become less prosperous and less territorially, economically, and socially cohesive. The situation would also lead to an increased regulatory fragmentation of the single market and a lower regulatory performance of the EU. The costs of this internal fragmentation have historically been paid by the varied internal crises that weaken the Union’s global position as a result. The logical challenge is to increase the EU capacity in delivering the cohesion policies and development funds oriented toward remedying the socio-economic, institutional, and infrastructural gaps. If the EU’s institutional and budgetary capacities are not proportionally increased, such enlargement costs could prevail over the enlargement opportunities.

The so-called statistical effect concerns the social and economic cohesion. Through this effect, the old net-recipient states – located mostly in the EU’s South and East – and regions would become statistically more prosperous after the enlargement, with the new(ly accessing) states and regions being statistically less prosperous. In 2022, the candidate countries’ GDP per capita in PPP remained under 50% of the EU’s average, and this figure includes the biggest three: Ukraine (29%), Albania (32%), and Serbia (44%). In other words, the current net-recipients would generally lose their positions or even become net-payers in the EU multi-annual financial framework (and the headings for cohesion and common agricultural policies), but without becoming more prosperous in reality.

To mitigate the negative costs of the statistical effect, the EU’s challenge is to increase its post-enlargement budgetary capacity and renegotiate the redistribution principles, e.g., in the EU Cohesion Policy. The EU’s developmental effect on cushioning the socio-economic divergence in the Union’s South and on supporting the socio-economic convergence in the bloc´s East would be otherwise severely weakened. For example, just for the EU-13, the EU cohesion funding covered 41% of their governmental investment spending over the three years from 2015 to 2017. The lasting impact of the last programming period of the cohesion policy investment can increase the GDP in these countries from 1% to 5% in the short term. Without any action, the EU internal cohesion can be undermined.

The costs of regulatory fragmentation are also a challenge to be avoided, namely by investing into increasing institutional capacities in the EU and individual member states. According to the World Bank’s world governance indicators (percentile rank 0–100), the eight candidate states score 43 points in government effectiveness and 48 points in regulatory quality on average. Georgia – the exception to the rule – scores 73 and 82 points, respectively. If the Visegrád states’ rankings were a threshold for sustainable enlargement indicators, this would require the candidate states to reach the V4’s regional average of 69 points in government effectiveness and 76 points in regulatory quality.

However, Albania’s 58 points in regulatory quality, making it the leader among the eight candidates in this regard, are close to the 64 points scored by the V4’s laggard Hungary. Meanwhile, Serbia’s 57 points in government effectiveness are close to the 61 points of the V4’s laggard Poland. The distances could thus be closed rather fast.

In sum, the enlargement would be a challenge for the internal cohesion of the EU in both regulatory and socio-economic terms. The challenge must be matched with a higher budgetary commitment and dedication to improving the institutional capacity on the EU level and in both old and new member states.

UKRAINE

Ukraine is, in many ways, a unique case, and therefore needs to be treated differently from the other candidate states. It is not just the size of the country, its potential internal market, and the fact that it has been a victim of Russian military aggression since 2014. EU membership is a cornerstone for the identity-building of Ukrainians as a new political nation defending democratic values and fundamental freedoms, which are in direct contradiction to Russia’s backward authoritarian kleptocracy. The EU membership can give a boost to the internal post-war development in Ukraine, while Ukraine could give the EU a boost to its soft power and geopolitical ambitions. We focus the present analysis on three interconnected categories: a) enhancing European security, b) geo-economic reinforcement and c) endorsing democratic values.

ENHANCING EUROPEAN SECURITY

The Russian re-invasion of Ukraine represents an unprecedented historical juncture for the EU, which now faces the most serious security crisis since its foundation. In this regard, Ukraine’s EU membership is an issue of strategic importance, closely linked to the country’s struggle for self-determination, independence, and sovereignty. Russia’s war in Ukraine shattered the illusion that security and stability in Europe come for free.

The Ukrainian army is now one of the strongest in Europe; it is able to withstand and contain Russian military advances, and might be a priceless piece in strengthening the fragile European security system, especially in light of the potential adverse consequences of the US presidential elections for Europe. The integration of the Ukrainian army into the European security system will contribute to the common European defence by special units (which is linked, for instance, to the operation of unmanned combat aerial vehicles). Ukraine can also contribute to containing the spreading Russian influence on a global scale – such as through a military cooperation against the Russian private military companies as successors of the Wagner Group in the Middle East and Africa.

Ukraine’s integration into the EU could also reinforce the production capacities of the European defence industry through the joint production of weapons and military equipment. The war has revealed serious shortcomings in Europe’s defence industrial production capacity. Depleted ammunition and equipment stocks paired with long production lead times betray a decades-long failure to plan for a high-intensity conflict.

Ukraine can be a laboratory for innovations in the defence industry through joint programs with Ukrainian engineers and designers with war experience. The business cooperation between Ukrainian and other European defence companies within the EU legislative framework could trigger new projects to enhance European military capabilities. Warexperienced Ukrainian companies can bring a lot to the table, while the rest of the EU needs to re-arm and reflect on Ukraine’s current experience from the war against the Russian invaders. Encouraging the development of joint ventures in the defence industry makes sense from not just a military perspective but also a business perspective. European defence companies, including the Ukrainian ones, can cooperate on the international level to push the Russian defence industry out of the global arms market, among other things.

GEO-ECONOMIC REINFORCEMENT

Geo-economically, Ukraine is essential for its deposits of natural resources. Ukraine has the second-biggest known gas reserves in Europe, around 1.1 trillion cubic meters and up to 5.4 trillion cubic meters if probable deposits are included (they are second only to Norway’s known resources of 1.53 trillion cubic meters). However, its gas reserves, as well as its other undeveloped and unexplored resources, remain largely untapped. However, the bulk of Ukraine’s critical minerals, especially the rare earth metals that are now in high demand, are found in Donetsk and other parts of Ukraine which are either occupied or threatened by Russia. Ukraine has commercially relevant deposits of 117 of the 120 mostused industrial minerals. The total value of such deposits – including those of titanium, iron, neon, nickel, lithium, and other key resources – could reach between $3 trillion and $11.5 trillion. Rare earth minerals (beryllium, tantalum, niobium, cerium, yttrium, lanthanum, and neodymium) and alloys are used in many devices people use every day, such as computer memory, rechargeable batteries, cellphones, and many more. Ukraine’s probable but unconfirmed reserves of lithium – a crucial input in electric vehicle battery production – could also be the largest in Europe. In the future, Ukraine might also be an important hub for the export of biomethane and green hydrogen – two key pillars of Europe’s future energy landscape – to the EU.

By jointly developing Ukraine’s natural resources and providing Ukraine with the necessary technology, European companies may lower the risks of dependence on authoritarian countries through diversification. In this scenario, Ukraine, as a member state, would access its own resources to finance the post-war reconstruction, while the rest of the EU would get access to resources at affordable prices to kick off the boom of industrial production. Ukraine’s accession to the EU would make the whole process more transparent, competitive, and accessible through a more favourable business climate as an outcome of de-oligarchization, anti-corruption reforms, and good governance measures. It would prevent European companies from contending with rent-seeking officials or a flawed judiciary incapable of protecting their assets. The degree to which the post-war reconstruction, financed by the development of natural resources, is successful would have a pronounced effect on European economies themselves. Ukraine’s large size and strategic location mean that recovery and future growth outcomes will profoundly shape the geopolitical landscape of the EU.

ENDORSING DEMOCRATIC VALUES

The resilient Ukrainian society shows a strong demand for fundamental freedoms and democratic governance. The war suffering lowered the tolerance of corruption in Ukrainian society, especially among veterans and soldiers, who expect that while they fight Russia on the battlefields, people and civic society will deal with the pervasive corruption in the country. There is a high demand for effective anti-corruption measures and a fight against corruption, which the EU could capitalize on as a partner in implementing anti-corruption measures. A poll taken in June 2023 shows that nearly 34% of Ukrainians consider government corruption to be a significant security threat in the coming months, against almost 24% who mention the risk of Russia using nuclear weapons as such a risk. According to other polls taken in 2022, the proportion of respondents who stated that they would participate in protests against corrupt officials at the national and local levels rose from 40% in 2021 to 80% in 2022.

Ukraine’s accession to the EU may help bring democratic values back to Europe on the wave of populism and the rise of emotions in the political life of many European countries, such as fear, which is instrumentalized by pro-Russian populist far-right actors. Ukraine could re-balance the rise of the pro-Russian fear-mongering populism in Eastern Europe and mobilize positive emotions by demonstrating that the values of freedom and democracy, which should not be taken for granted, are worth fighting for.

THE TIMELINE OF UKRAINE’S ACCESSION

To conclude, the accession of Ukraine may boost the geopolitical position of the EU on a global scale and enhance European security, geoeconomics, and common values. Europe would get one of the world’s strongest armies, which would be able to contain the Russian expansion and strengthen the security architecture, and priceless resources, which would help to overcome dependencies on aggressive authoritarian regimes. The accession would also rebalance the wave of anti-democratic populism by endorsing the common democratic values. Ukraine’s EU membership could also boost the Ukrainian economy and post-war reconstruction as it would lead to tapping its natural resources and implementing domestic reforms.

A timely accession is important for the internal stability of Ukraine. A lengthy accession process may destabilize state institutions, undermine the position of the current government, cause disillusionment within Ukrainian society, and provide persuasive arguments in favour of the Russian propaganda. In this propaganda narrative, democratic and pro-EU Ukrainians will be depicted as naïve fools who drove the country into the war with Russia in 2014. Also, Russian propaganda and domestic populist forces will disseminate another narrative: that Ukrainians will never be “good enough” for Europeans while Russia is ready to accept them as they are, so it makes no sense to break into the locked door while Russia is ready to open it for Ukraine despite the war destruction.

THE WESTERN BALKANS

The Russian invasion of Ukraine has brought a new sense of urgency into the EU-Western Balkans (EU-WB) relations, while stressing the EU’s weakened credibility in the region. The ongoing conflict has fundamentally changed the geopolitical landscape surrounding the enlargement process, presenting an opportunity for a re-evaluation of the future of the EUWB relations. The full-scale war in Ukraine that started in February 2022 has disrupted the long-standing stagnation of the EU-WB relations, introducing a mix of risks and unforeseen opportunities.

RISKS

Political dynamics: The war’s impact on the region includes the activation of Russian proxy actors, which could potentially destabilize the Western Balkans. Although Republika Srpska’s secessionist rhetoric has been less vocal since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the tensions between Kosovo and Serbia persist, raising concerns about a possible further escalation.

Structural challenges: The Western Balkans face economic stagnation, demographic decline, and governance issues. The lack of a clear path forward fosters ethnonationalist sentiments. The region also stands as a migration route from the Middle East, which is expected to expand due to ongoing conflicts and climate change. Organized crime has been exacerbated by the Russo-Ukrainian War as well.

Internal and bilateral disputes: The ongoing disputes between Serbia and Kosovo, Bulgaria and North Macedonia, and Bosnia and Herzegovina’s entities hinder progress and, at times, breed instability.

Socioeconomic challenges: The war has already led to war-related inflation, food, and energy shortages, and worsening economic conditions in the Western Balkans. The severity of the social crisis will depend on the war’s duration, local responses, and the EU’s reaction.

Information disparities: The coexistence of conflicting narratives about the RussoUkrainian War has deepened the political divide in the Western Balkans, creating disjointed information and moral worlds. The polarization is likely to have a negative impact on attitudes toward EU integration, and addressing it will require smart and targeted strategic communication by the EU and NATO.

OPPORTUNITIES

Geopolitical momentum: The Russo-Ukrainian War has revived the EU enlargement process. The EU, driven by the need for geopolitical alignment and security cooperation, is more open to involving the Western Balkans in energy and security cooperation, and most Western Balkan countries have expressed interest and support for these initiatives. The EU has signified its commitment by commencing negotiations with North Macedonia and Albania, and by the December 2023 decision to open membership negotiations with Ukraine and Moldova and to grant candidate status to Georgia.

A possible decline in destabilizing elements: The current state of the war favours the Ukrainian defence and weakens destabilizing elements, reducing the influence of Moscow’s clients, narratives, and symbols across the Western Balkans. This, in turn, diminishes nationalist narratives.

Local dynamics: Some Western Balkan countries, such as North Macedonia, Montenegro, Kosovo, and, partially, Albania, exhibit a dynamic development and align with EU and NATO aspirations and reform agendas.

However, these opportunities are transitory, and susceptible to changes in the geopolitical landscape. Factors like war escalation, winter energy shortages, EU disunity, or shifts in the war’s trajectory could alter the current favourable conditions. This moment represents a geopolitical momentum rather than a permanent shift, emphasizing the need to act promptly to prevent risks from eclipsing opportunities.

THE EU RESPONSE

Neglecting the momentum generated by the war risks amplifying existing threats to regional stability through the EU’s stagnant approach. Simultaneously, the EU integration process, while a legitimate political aspiration, easily becomes a facade for many, allowing local elites to maintain autocratic rule without facing repercussions, thus undermining sincere reform efforts. To ensure the preservation of the EU’s image as a values-based project in this changed geopolitical context, it is imperative that the EU carefully assess and adapt its strategies for engagement with the Western Balkans. This should involve a more nuanced and balanced approach that would prioritize both security and the promotion of democratic principles and institutions.

The countries that have advanced the furthest in the negotiation process, Montenegro and Serbia, get to open new or close previously opened clusters. For North Macedonia and Albania, the accession talks officially begin on a technical, not only a political, level. The candidate status is confirmed for Bosnia and Herzegovina, and the citizens of Kosovo gain access to visa-free travel. In a positive scenario, the geopolitical approach can allow the EU to eventually facilitate the agreement on normalization of relations between Kosovo and Serbia. It can further allow BiH to get through a serious institutional transformation based on a compromise between all three sides as a price for preserving stability at any cost.

Montenegro and North Macedonia remain under Western influence, with the US and NATO in the driver’s seat as the main political force.

There are two potential pathways for EU-Western Balkans relations:

GEOPOLITICS AND LONG-TERM DEMOCRATIC SECURITY

Considering the escalating threats, EU states prioritize a strategic realignment and a security collaboration with the Western Balkans (WB). One example of this is the establishment of the European Political Community (EPC) as a platform for engaging the WB in strategic dialogues. Formats such as the EPC can facilitate political consensus on addressing crises and risks stemming from the war in Ukraine, including political instability, inflation, and energy dependency across Europe.

If the WB region maintains its overall stability, the EU’s geopolitical approach has the potential to facilitate a Kosovo-Serbia normalization agreement and assist in Bosnia and Herzegovina’s institutional reforms. Meanwhile, Montenegro and North Macedonia are expected to remain firmly on the European path. There may be some favourable conditions for a geopolitical approach to the Western Balkans: the diminishing influence of other external actors, such as Russia and China, and the region becoming a buffer for Middle Eastern migrants, as well as a key source of green energy projects for the EU.

Thinking of the risks, while the EU is increasingly adopting a geopolitical stance in the wake of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, this pathway does not effectively address the risks stemming from the war in Ukraine and leaves the structural risks in the Western Balkans largely unaddressed. EU representatives have, at times, inadvertently legitimized autocratic regimes in the Western Balkans at the expense of strengthening democratic institutions and encouraging reforms. In the long run, this geopolitical approach, while generating support for the Western Balkans’ accession, can result in a series of inconsistencies within the enlargement process.

The engagement with questions concerning EU values, rule of law, and mutual trust seems inevitable regardless of the geopolitical context brought forth by the war in Ukraine. Such engagement can be easily compromised by forms of legitimization of autocrats that may come at the expense of institutional reforms. Even though the war has brought about extraordinary political circumstances, compromising the advancement of rule-of-law reforms brings risks of inconsistency in the Western Balkans-EU relationship that can have a negative impact on the mutual trust, as well the legitimacy of the EU in the region.

Democratic backsliding and authoritarian practices continue to be tolerated by the EU as a means of maintaining relative stability in the region. This is manifested through the lack of attention to corruption and state capture, as well as the damages to the media freedom in Serbia, for example.

What could be seen as an example of such an approach is the visit of European Commission’s President Ursula von der Leyen to Bosnia and Herzegovina and Serbia in October 2022. The political messages of this visit were criticized by analysts as dangerous: On Twitter, von der Leyen stated that ‘Serbia is well advanced on its EU path’, while according to her own 2022 Country Report, the country is only ‘moderately prepared’ and this conclusion has not changed since 2016. The visit of the EC’s president was a significant display of European solidarity in a time of war in Europe and provided the region with an inconsistent narrative regarding the state of reforms in Serbia. Thus, it is important to answer the question of how the accession criteria can be integrated in a geopolitical approach that is long term and strategic, but not a product of short-term political gestures. Facilitating enlargement as a reform process and asserting its conditionality are the EU’s long-term goals regarding the Western Balkans and as such they have to be communicated to all governments, including those that legitimise autocratic practices and corruption and do not comply with EU values.

ENHANCING THE EU ENLARGEMENT POLICY WITH NEW MEANS

This pathway advocates for the modernization of the EU enlargement policy through the introduction of innovative approaches, while considering the evolving geopolitical context. Such innovations could entail a gradual step-by-step accession with clear deadlines, and greater support for democratic institutions, civil society, and economic development in the Western Balkans. In this situation, the EU underscores rule-of-law reforms as a central accession condition and embraces a credible strategy that includes qualified majority voting to prevent individual member states from obstructing the process. The improved technical aspects of the accession process introduce tangible incentives for progress while maintaining clear drawbacks for any backsliding. The EU did tolerate Bulgaria’s unconstructive approach toward North Macedonia by placing most of Sofia’s argument at the core of the accepted French proposal. The expediency will be costly, as it discourages and possibly limits the chances of the only Europe-oriented WB government in the next elections, since the decision to accept such an agreement was highly unpopular. Meanwhile, the EU was unable to persuade Serbia and parts of Bosnia’s nationalist elite to support its foreign policy on Ukraine.

However, the accession process cannot be dependent on electoral changes and if new pro-European parties struggle to gain and retain power, this may lead to political crises.

While the EU will be able to reward the progress in some countries, skepticism is likely to persist in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina, threatening to result in turbulent politics and a divided EU stance. Despite substantial investments, the EU may fail to stimulate a stable democratization and reforms in all the WB states, which could result in some turning to alternative geopolitical partners. Rival powers have shown their potential for disrupting regional stability, encouraging unresolved disputes and identity politics, and hindering the countries’ readiness for accession. Thus, prolonged reforms erode the EU’s credibility, diminishing its stabilization role and escalating unresolved conflicts.

The direction toward a geopolitically oriented policy toward the WB is necessary and a good start, but this approach ineffectively addresses the risks induced by the Russian war in Ukraine and leaves all the other structural risks in place. It further risks continuing the status quo. If the EU intends to seize the opportunity of the geopolitical momentum in order to make headway in its policies regarding the WB, and if the EU wants to be a value based project, it needs to find the means to do it. Focusing on the geopolitical momentum should mean neither a shortcut to membership nor a baseless political support from EU politicians for local governments. This approach may bring some short-term political gains but risks undermining the EU reform drive in the region.